Beneath a Bustling University Campus, a Big Cable Is Listening

Bloomberg CityLab

05.30.2017

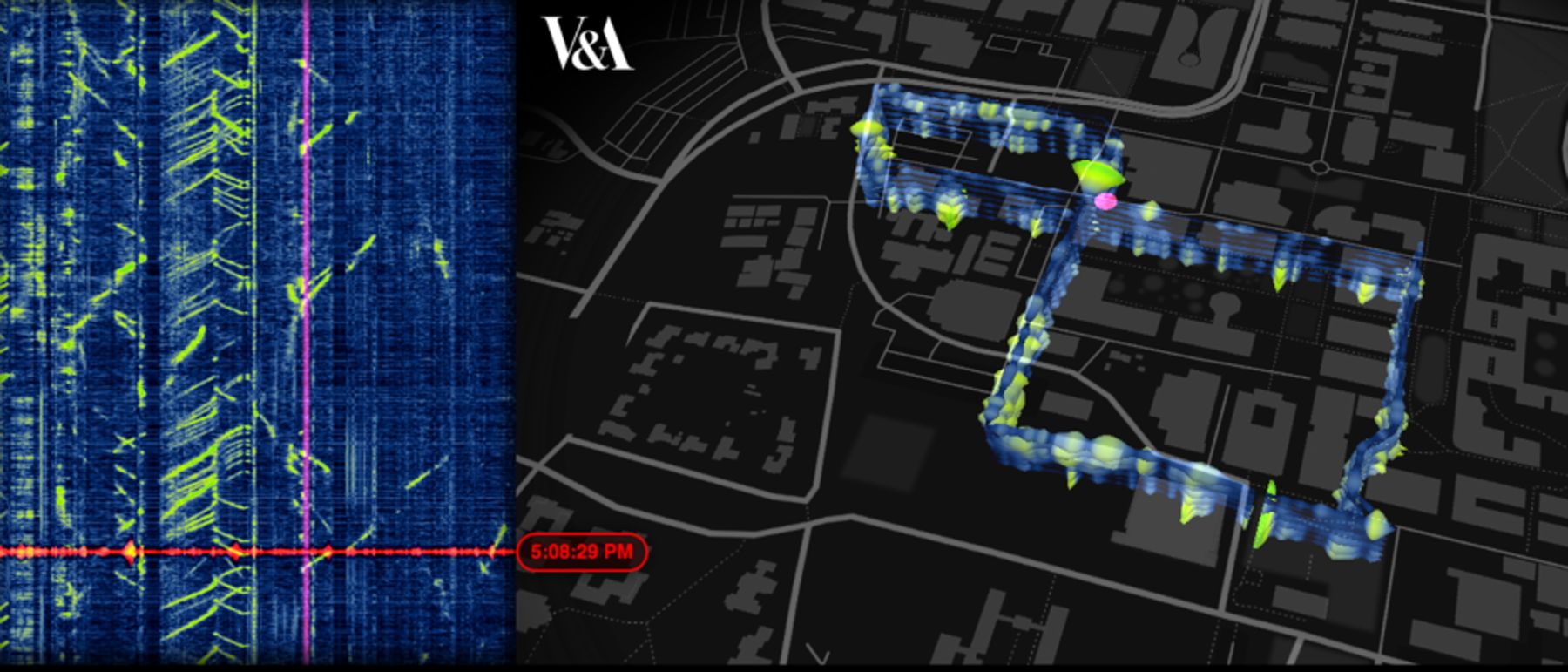

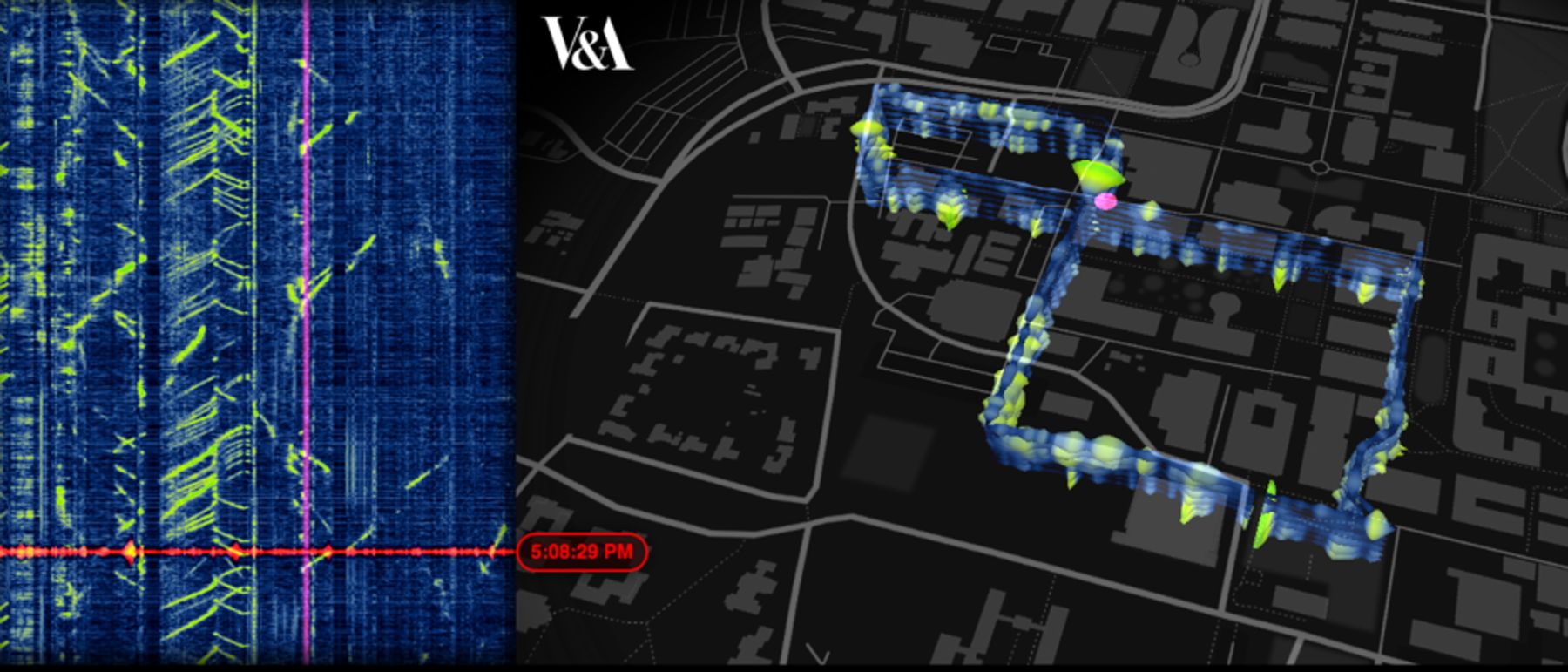

The project is called “Big Glass Microphone,” and it’s an interactive, online visualization of the acoustic vibrations picked up by a fiber-optic cable buried beneath a road at Stanford University. Normally used for earthquake detection, the three-mile cable inadvertently gathers other kinds of data, including the sound of objects moving above ground. Campus seismologists filter out those wavelengths, but Stamen Design, a San Francisco-based map design firm, joined with London’s Victoria and Albert Museum to yank them out and map them.

The result is a curious figure-eight blob, composed of neon-colored horizontal bands that undulate over the course of ten minutes of a late afternoon on campus. The bands represent distinct frequencies of vibration, which Stamen traced to different kinds of traveling objects; you can separate and examine them closely at different moments in time.

Cars driving along the road activate several frequency levels, and show up as big bursts of green on the top strip. Pedestrians and cyclists show up as smaller, dynamic swells. A stationary fountain “sends out a more or less constant vibration of between 160–300hz, a bit higher than a human voice,” according to the project’s website.

At a larger scale, imagine how valuable this type of data would be for an engineer corralling traffic, or a mobility service sniffing out customers. Big Brother could “listen in” without even putting extra sensors in place. Rendered as brightly colored blobs, though, the sounds could also be understood and manipulated by you, the person who might generate them to begin with. Perhaps some of the “incidental microphones” of our brave new world could be held by people, artists, and thinkers, says Eric Rodenbeck, Stamen’s founder, CEO, and creative director.

“I don’t want to shout about technological determinism,” he says. “If we look at this stuff less as an object of terror, and more as an artifact of our world, then we can have conversations about what’s possible for us to do with it.”