Today (January 22nd) is Treaty Day in the region where I live (the northwest part of Washington State). It marks the day in 1855 when the Point Elliott Treaty was signed between the United States government and the native nations living around the north part of Puget Sound (the central Salish Sea).

I talked a little bit about the importance of understanding and honoring native treaties in a presentation I gave a few months ago at the North American Cartographic Information Society conference in Tacoma, Washington. The video of the talk was posted a few months ago (which you can view on YouTube) but today I’m posting a transcript of the presentation along with images of the slides, for those of you who’d prefer to read rather than watch the video.

The talk begins here:

I’ve been working with OpenStreetMap (OSM) for quite a long time, for work, for research, for personal interest. And today I’ll be talking about about Native Reservations in OpenStreetMap. This will be a bit about what native reservations are, and why they’re important, but also how we go about the process of collaboratively editing the map on OpenStreetMap.

In this presentation I’ll alternate between a very practical story about OSM, an another story that’s about the why of this project.

Before I begin, I’d like to acknowledge that we’re gathered here on the traditional and ancestral lands of the Puyallup Tribe and here on the Salish Sea, the greater region we are on the lands of the Coast Salish people who have been here for millennia. Everything we do here is on their land. [side note: never heard or done a land acknowledgement before? Read: A guide to Indigenous land acknowledgment]

We are also as cartographers here, part of making maps, working with “open data” in this session. I’ll be talking about OpenStreetMap. For those of you who don’t know what OpenStreetMap is, it’s a collaborative map of the world. Anyone can edit it, anyone can change any feature that you see on the map, you can add something, you can remove something; it’s kind of like Wikipedia, but for maps.

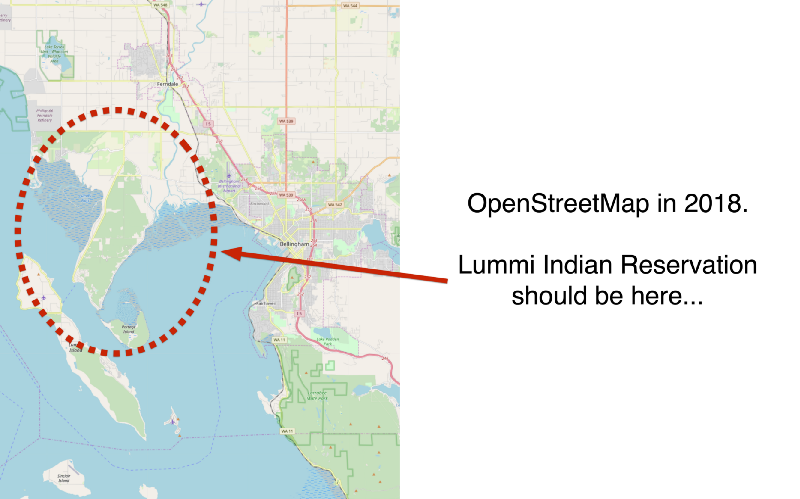

I live now in Bellingham, Washington. It’s where I was born and raised, and I just moved back there a few years ago. It’s also on the traditional lands of the Lummi and the Nooksack people. And here in Bellingham there is a fairly large native reservation right across the bay from us. I was looking at OpenStreetMap sometime last year — I’m always looking for things to add to the map to contribute to OSM — and I noticed that our local native reservation was not on the map. “Great,” I thought, “I’ll find some open data that I can put into OpenStreetMap and I’ll add it.”

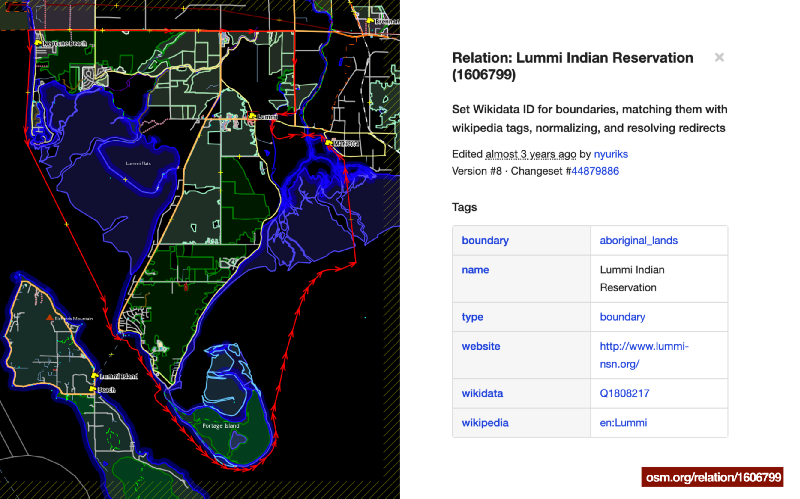

So I opened up the JOSM editor which is one of the multiple tools you can use to edit the OSM database. And as soon as I open it up, I see that the reservation already was there!

Now, ignore that this map is a little bit ugly. This is the power-user tool for editing OSM which lets you see all the attributes and all the history of every feature in the database. I can see that it already exists, someone already added all these “tags” describing that it is a boundary feature of type aboriginal_lands. They’ve linked it to the Wikipedia page. And this was already version 8 by the time I saw it, and it had been created over eight years ago. So this has been in OpenStreetMap for a long time, but it’s not been on OpenStreetMap. What does that mean? What’s going on here?

The thing is, OSM is less of a map, and it’s more of a database. That’s the fundamental thing about it: OSM is a collaborative database, and there are many possible maps that could be made from this data. But there’s one particular map that lives on the openstreetmap.org website, and this is basically the “default” map. You kind of want to show up on that map.

So in a moment I’ll come back to this point, and we’ll figure out how is it in the database, but not on the map.

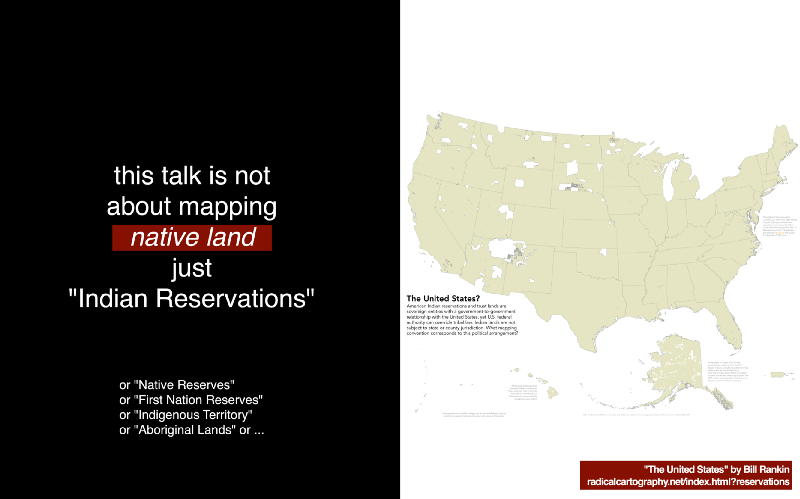

But in parallel to talking about OpenStreetMap, I want to talk about what it is that we’re actually trying to map here. I want to be really clear that I’m not really talking about mapping native land, because in a sense this is all native land. And I’m not talking about “indigenous mapping”, that is, mapping things form a native perspective. I’m not native, I’m not indigenous, it’s not my place to talk about those things. Really I want to find a way to contribute that is true to my perspective, and true to something I can meaningfully contribute about. [I also forgot to add: Often, there are many reasons why certain native sites and indigenous geographic knowledge should not be mapped at all.]

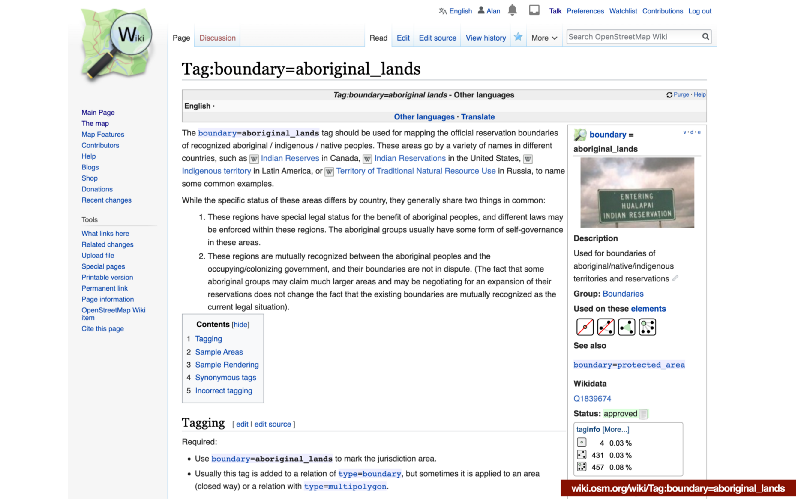

So I’m talking strictly about mapping this legal concept of “Indian Reservations”, and of course in other countries they’re called a lot of different things: “native reserves”, “first nation reserves”, “indigenous territory”, “aboriginal lands”, etc. So there are a lot of terms for these kinds of things, and I may use these terms interchangeably, but what I want to emphasize is that this is not an “aboriginal mapping” exercise.

So, looking into OpenStreetMap, the first thing we need to do is figure out what are these features that are already in the database, and we also need to figure out what tags are actually being used in OSM. So there’s this tool called “Overpass Turbo” where you can do queries that are basically database queries where you can say “show me all the things in the database that have these tags.” In OSM tags are key=value pairs and you can attach any number of them to any feature. And in OSM it’s a free-for-all in terms of which features you use.

And I found that there were two main ways that people were already using to tag these features in OSM. One method that was mainly used in Brazil was this tag boundary=protected_area with a secondary tag protect_class=24 which comes from some UN classification scheme somewhere (I think).

Then there’s also people mostly in Canada who are using boundary=aboriginal_lands instead. Either of these seem to be potentially legitimate tags that we could use.

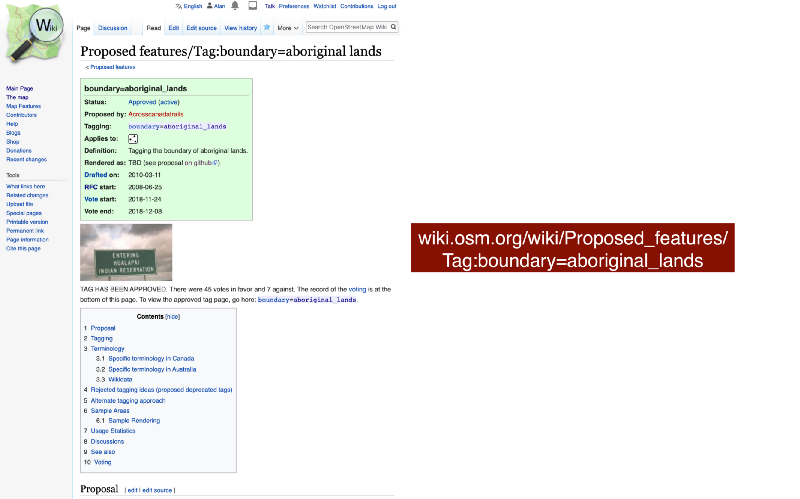

I also went digging around in the OpenStreetMap Wiki. This is separate from wikipedia, but it uses the same wiki software, and this is where all the collective knowledge and documentation of OpenStreetMap lives. And I found that there’s a proposed tag that someone had proposed back in 2010. But the person who proposed it later left the OSM project and didn’t carry that proposal through to an actual discussion and any kind of approval within the OSM community.

And here I should also clarify that even though I said it’s a free-for-all, there are sort of rules within OpenStreetMap. There is certainly consensus on some specific tags that you should use to describe certain features. It’s like “this is kind of the ‘right’ way to tag something. We can’t really stop you from using any tags you want, but if you create your own tags and put them into OpenStreetMap, no one else will know how to use those tags or interpret them.”

So there’s definitely consensus on some things, and there are some tags that have been voted on by the community where it’s been decided that this is the official way of doing things.

One of the ways you get a tag approved is to write up a description of your tag in the wiki, then you send an email to the OpenStreetMap mailing list saying “I think this is a good idea, here’s why. Does anyone have any concerns, let’s talk this out, and then eventually we’re vote on it.” So basically I found this proposal that already existed and it just needed a nudge.

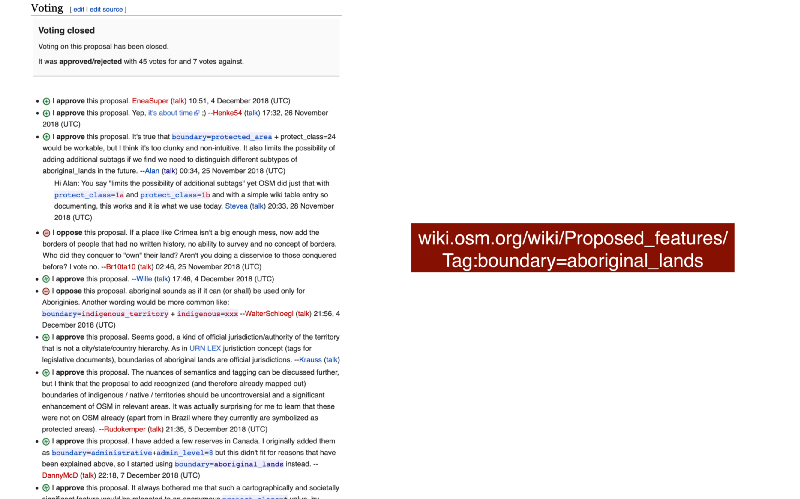

We had a nice long discussion on the mailing list, and in the wiki. Mostly people were in favor. There were some people who had comments like “maybe this other tag might work”, or “have we thought about this other thing?”. There were very few people who were completely against the idea, although some people thought “really this should be treated just like any other kind of administrative boundary” like for cities or counties.

[side note: Of course most of the discussion was in English, which is a serious weakness of the part of the OSM community where decisions get made. We need to do better in that regard and include more people who speak other languages.]

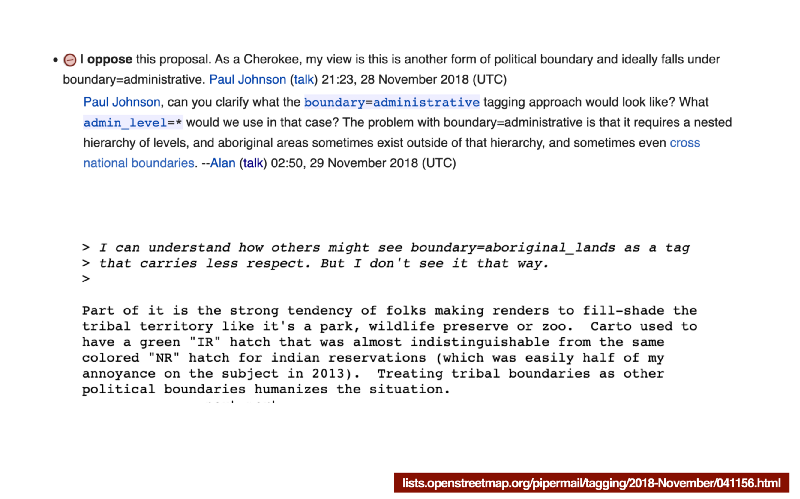

Even people who identified as native had different opinions in this discussion. This is a good reminder that there’s no single voice we could be listening to about how it ought to be done from a native perspective.

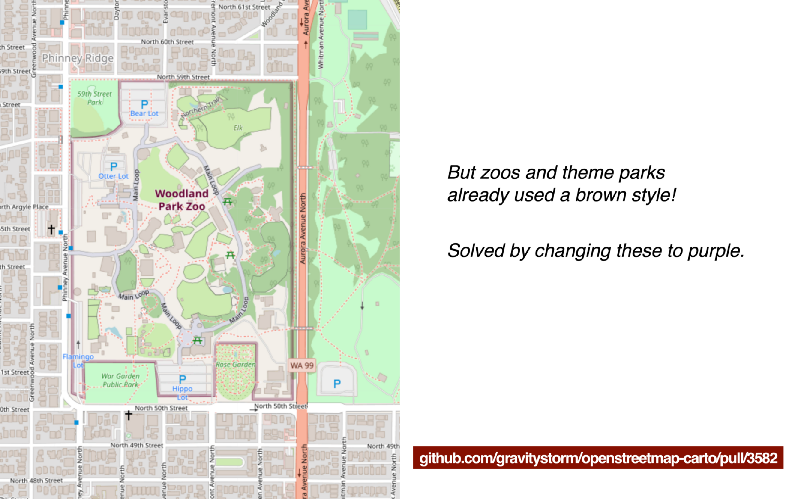

One person who identified as Cherokee thought we should just find some way to fit this into the already-existing administrative hierarchy rather than giving reservations their own tag. But then he clarified that the main reason he was concerned about this is that in the past people had tried this in OSM and they just colored native reservations on the map just like a nature preserve or a zoo. In his view, he’d rather not be drawn with any distinct boundary color at all if it’s going to be the same as a zoo or a nature preserve.

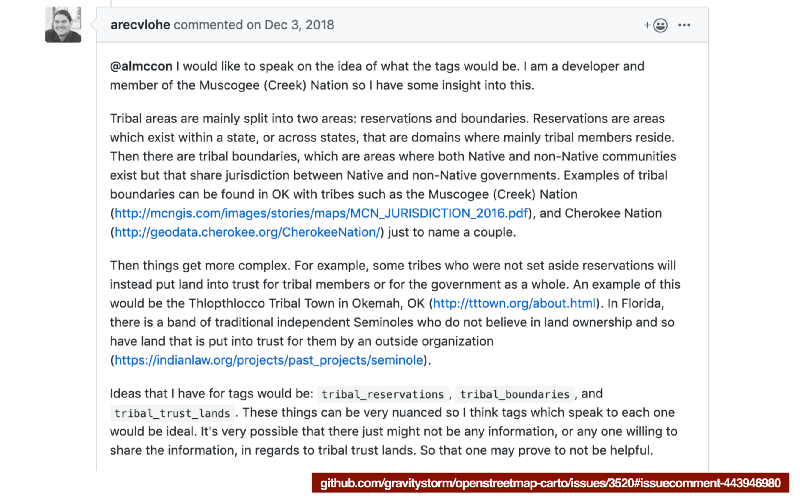

Another contributor from the Creek nation pointed out that it’s probably even more complicated and we need maybe three different tags instead of just one. The good thing with OpenStreetMap is that we can always add more detail later.

So after the discussion and voting, we decide we’re going to “approve” this tag boundary=aboriginal_lands which has already been in use for at least eight years, and we’ll also approve the other tagging with boundary=protected_area + protect_class=24.Basically, you can use either one, and we will just treat them as synonymous tags to describe the same thing. But at least they’re all officially approved now.

So now that we’ve got them approved in the database, we can start talking about how to get them displayed on the map. We’ll come back to that in a moment.

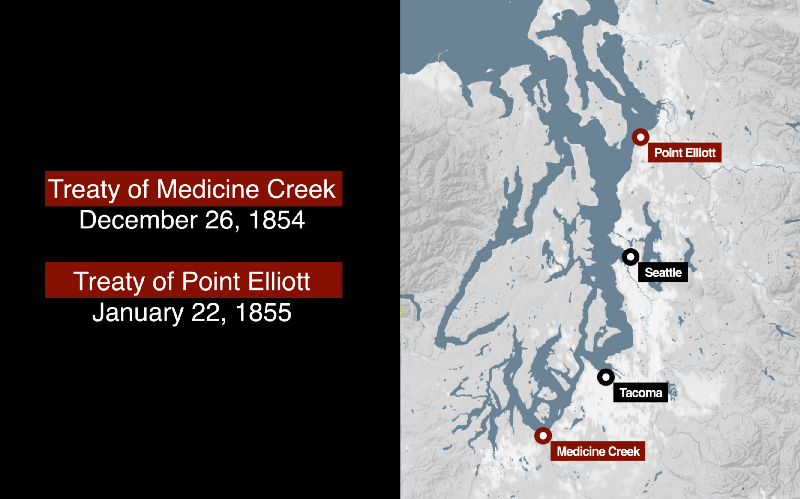

So I’d like to switch back to thinking about these things that we’re trying to map, and why they’re important. So here in the Puget Sound area along the Salish Sea, there were two main treaties between the settlers (the United States, the Territory of Washington) and the native tribes in the area. One was the Treaty of Medicine Creek which is near present-day Olympia. This was the treaty with the Puyallup tribe that lives in the lands here in Tacoma [where the conference was held]. And for most of the northern part of Puget Sound and the central Salish Sea, including the current city of Seattle and Bellingham where I live, there was the Treaty of Point Elliott.

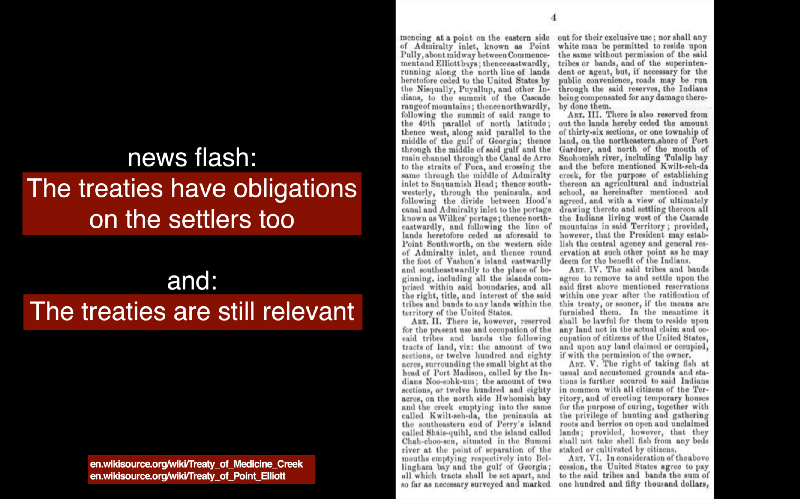

Why are these important? These are basically the founding documents that make our lives as settlers here possible on these lands. These are at least as important as the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, but we’re not taught about these things. I grew up in this area and these were never talked about. There were these treaties between us as settlers the native people as sovereign people, as equals, and that is why we are “allowed” to be here.

Now OF COURSE these treaties were signed under threats of violence, they were made between two cultures that had extremely different ideas of property and ownership, and they probably weren’t even correctly translated. And even if all those criteria had been met, of course the settler culture wasn’t really following up on their obligations after signing them anyway.

So there are so many things that are wrong and flawed in these treaties. But, if we want have any baseline for what it means to have real mutual relations with our native neighbors, how do we begin having any kind of ethical life here as settlers, the bare minimum is to understand these treaties, to respect them, and try to follow them as best we can.

And news flash: these treaties were not just “ok, now we get your land.” There were obligations to the settlers too. For one, the native people were allowed to continue to fish and hunt in all of their traditional territory. And also that the United States was responsible for supporting the welfare of these reservations and the people living on them. This was the exchange, the price for this deal. And these treaties are still relevant and in force today. The Lummi Nation (the one next door to Bellingham) was recently able to use their treaty rights to stop the construction of a new coal export terminal. So in a way that all the environmentalists in the settler culture had no legal basis to stop this climate crime of exporting more coal, the treaties that were still in force with the Lummi were able to stop it.

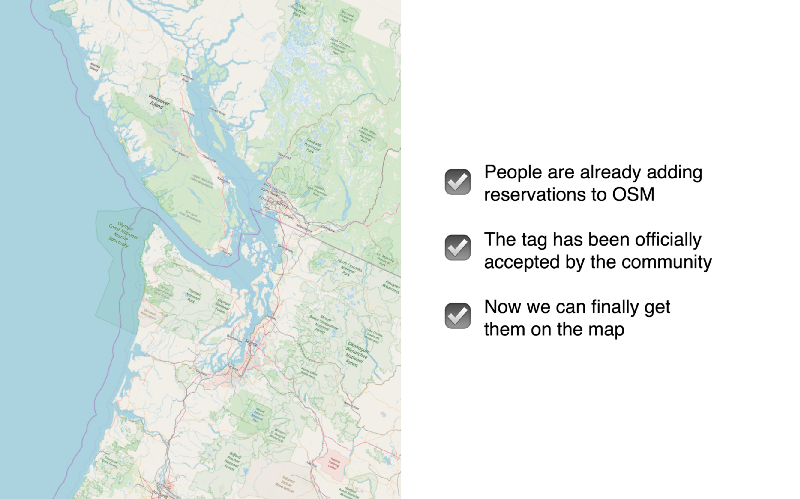

Okay, so going back to OpenStreetMap, here’s where we are: People are already adding these reservations to OpenStreetMap, now we’ve officially gotten these tags recognized by the community, and now we’re ready to finally get them on the map. We can go to the maintainers of the OpenStreetMap default map style and get them to add these things to the map.

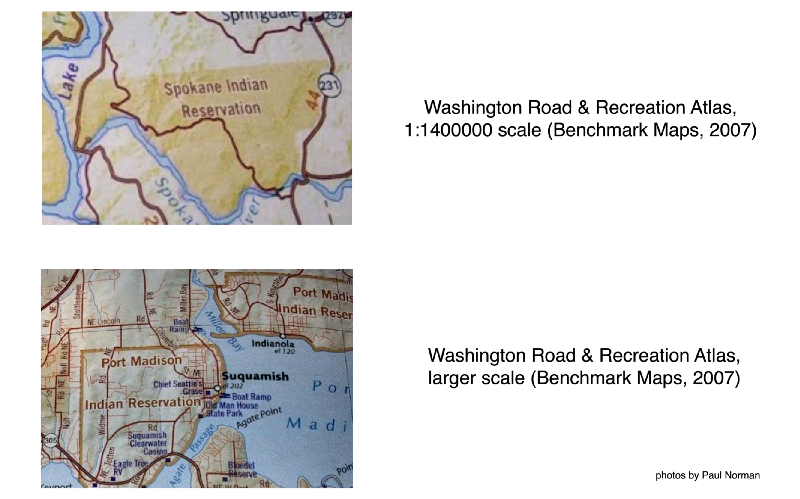

In OSM the basemap style they use is not really trying to invent anything new. As much as possible we’re trying to use cartographic conventions that are already well-used. Here are some photos from Paul Norman who started looking through a bunch of print atlases that he had, to see how reservations are already shown on maps. They were almost always shown in brown, styled differently depending on whether it’s a small scale or large scale map.

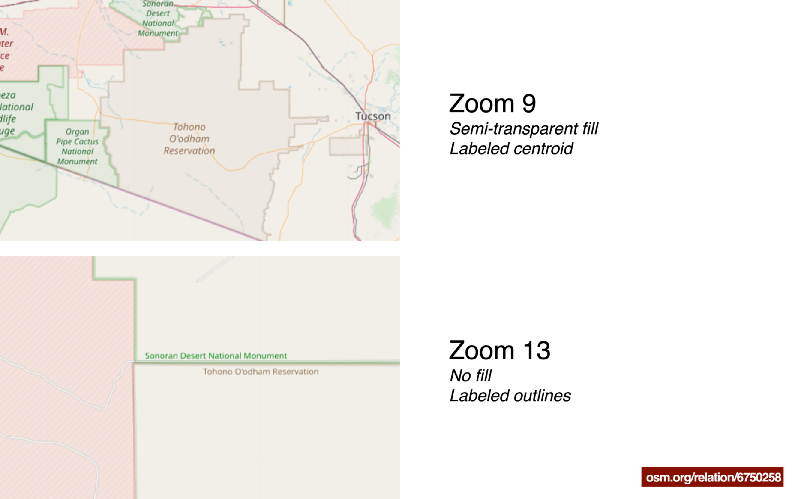

That’s because reservations are a tricky thing: when you zoom out, you usually want them to be rendered as a large color field across the landscape. But when you zoom in, you don’t want that color field to be disruptive and distracting when you’re looking at smaller features like roads and buildings. You just want to indicate the boundaries at that point, you don’t really need a fill. So we tried to replicate that in OpenStreetMap.

It was actually quite easy, we could just copy a lot of the styles that were already being used for nature reserves and parks, but make sure we give them their own color and their own adapted style so that it’s completely clear that these are not nature reserves.

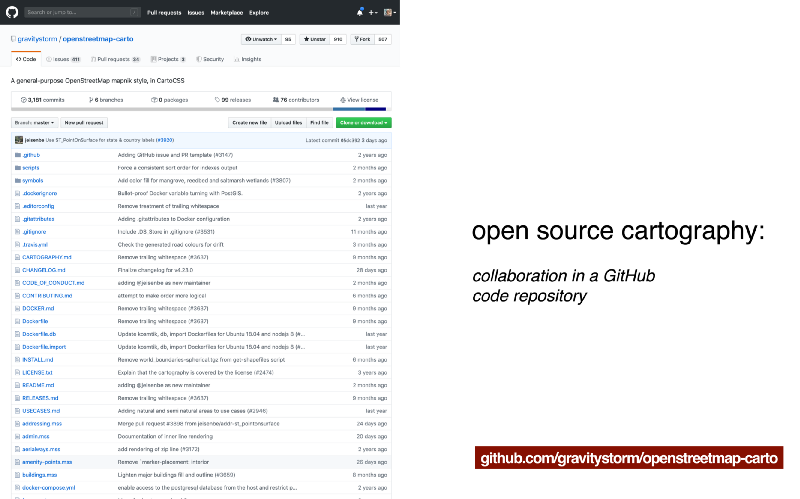

If you want to do any collaborative cartography with OSM you have to get a little bit familiar with github which is the code repository where the style lives. Go ahead and dive in. In order to make change and collaborate, you need to download your own extract of part of the OSM world. The whole database for the entire planet is too big to work with. I started just by downloading Washington State. After that it’s a bit of a steep learning curve to get the style running; there’s software called Docker which you can download onto your computer and it does most of the work for you. It makes a whole copy of all the software needed to run the rendering infrastructure for OpenStreetMap. Then you can just try changing a single line of code and see what happens.

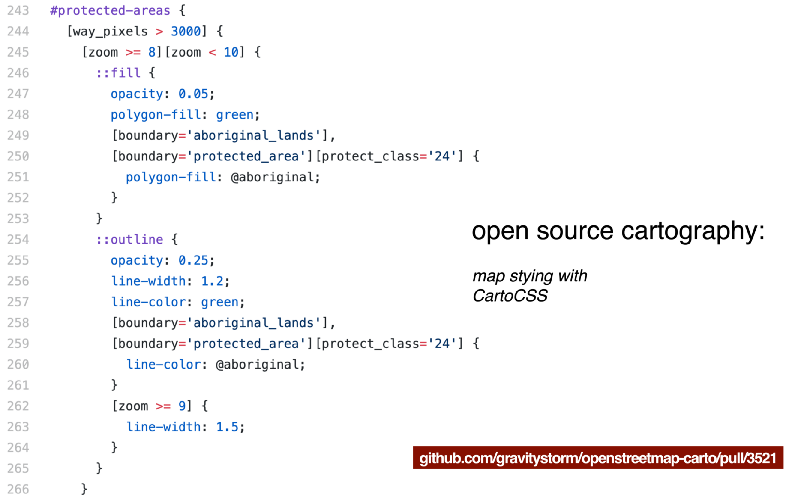

We use CartoCSS which is like CSS style sheets for the web, but specifically for cartography. The reports of the death of CartoCSS have been greatly exaggerated. It is still in use. Here is a snippet of the code that makes these protected areas possible.

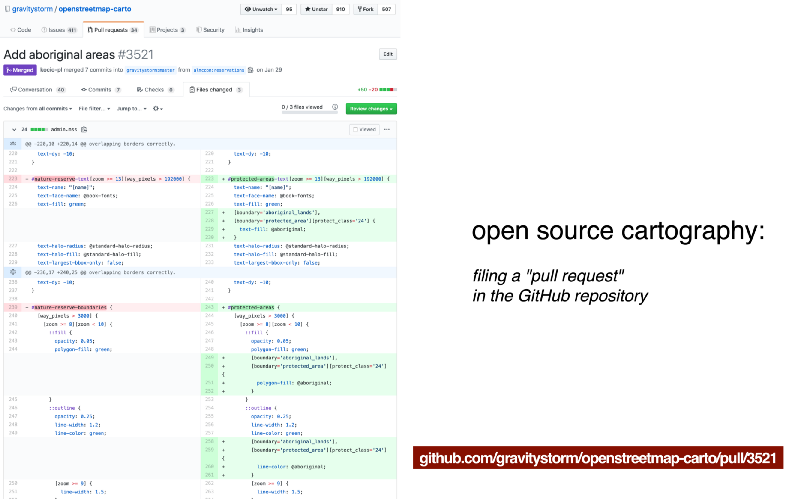

Once we make that change and we tested it on our computer and we think it looks good, we create a “pull request” saying “here are the lines that I want to change, does this look okay?” and other contributors to the map style will look at it and test it and decide if it looks safe to pull into the main branch of the code repository.

And while you do all these steps, there are many other contributors to the OSM style who are very helpful, but they won’t do anything for you. They might comment with a suggested change, and it might be a one line change that they could easily fix for you, but they’ll say “could you change this and resubmit”? Which is great, it’s a good learning experience as well. They are very helpful to answer any questions, but you have to push your pull request along yourself.

But of course, in the process of checking out our proposal, we realize that yes there already were zoos that were using the same color that we wanted to use for native reservations. We realized we were about to do exactly what we were told not to do. So we paused the pull request for a little while, and luckily there was other work going on in other parts of the style to change around some of the other colors. They were already working to combine the colors for zoos and theme parks, and they changed those to purple, freeing up the brown color that we wanted for the native reservations. So there are a lot of moving pieces when you’re collectively working on a style with many people all working on different parts of it simultaneously.

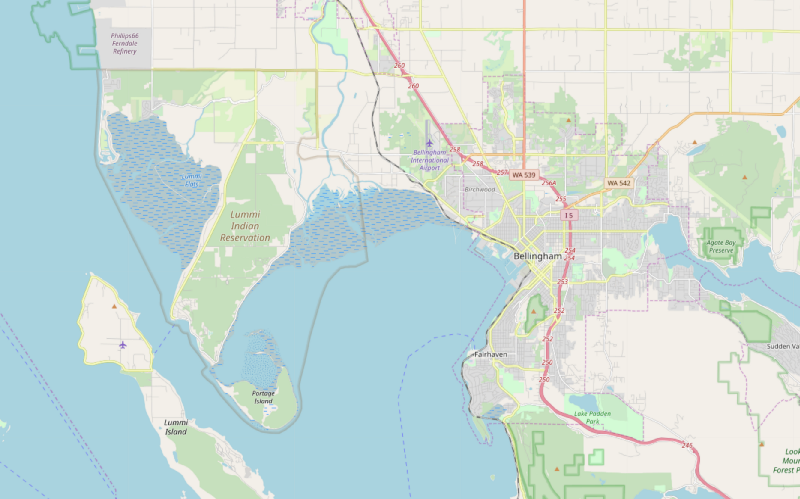

So then we got the pull request approved, and now there are reservations showing up on the map! Here’s the Lummi Nation in my neighborhood.

Here are some on both sides of the border between Montana and Alberta.

Here are some in the Amazon of Brazil, where they were incorrectly using nature reserve tags and showing all of these in green. Now we can surface the correct tags and color them differently, so you can see which areas are indigenous reserves and which are biosphere reserves.

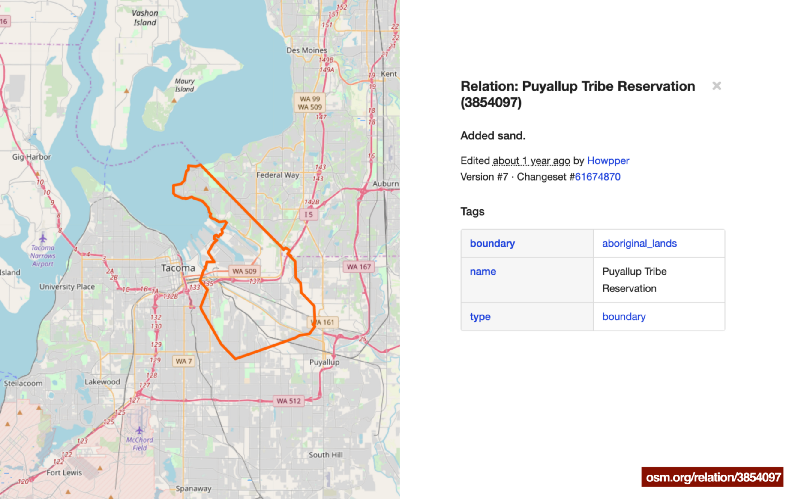

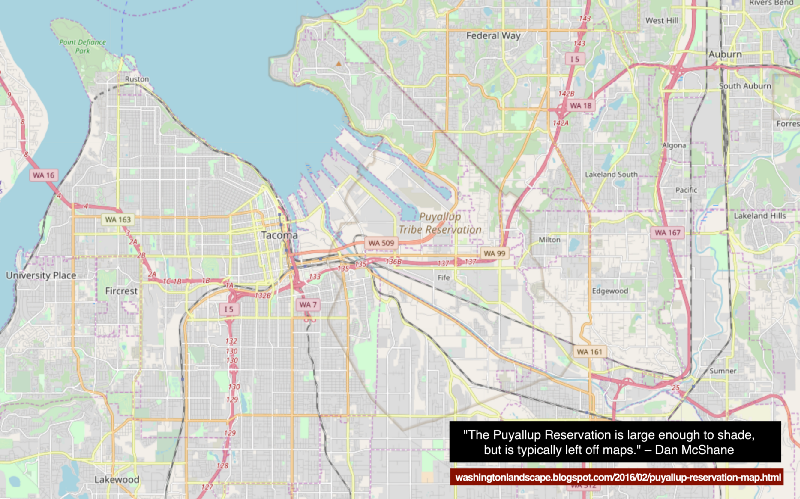

And now we get to reveal why mapping native reservations are a bit of a challenge, and why a lot of cartographers would prefer to avoid the problem and ignore them. And it’s probably why we haven’t gotten these reserves on the map before. Here’s the Puyallup reservation which is the one right across the harbor and including most of the port.

For those of you who live around here you might be surprised at the extend of this reservation. Most of it is suburbia. Most of the land in this reservation has been bought up by non-natives over the last 150 years, and it’s barely noticeable as a reservation on the ground anymore, with few signs showing when you’re entering or leaving it. To quote: “The Puyallup Reservation is large enough to shade, but is typically left off maps”. So you’ll see a lot of maps of Washington State where they’ll map every other reservation but this is one where they’re like “ehh, this is a little too complicated, a little too mixed up in an urban area” and so they’ll ignore it. So now OpenStreetMap is showing that this reservation exists, it’s a real thing, it’s actually meaningful, it’s a real treaty that we have to uphold.

“The vast majority of the Puyallup Reservation is owned by non Indians. The buying up of the Reservation took place in the late 1800s via the Reservation being allotted into parcels to individual tribal members. Those members then lost their land through a series of illegal lease agreements that were converted to sales with the approval of Washington State with misleading reports to the U.S Congress. However, the Reservation boundaries remained in tact and are still recognized and has driven and continues to drive policy and land use in a very heavily urbanized landscape.” — Dan McShane, Reading the Washington Landscape

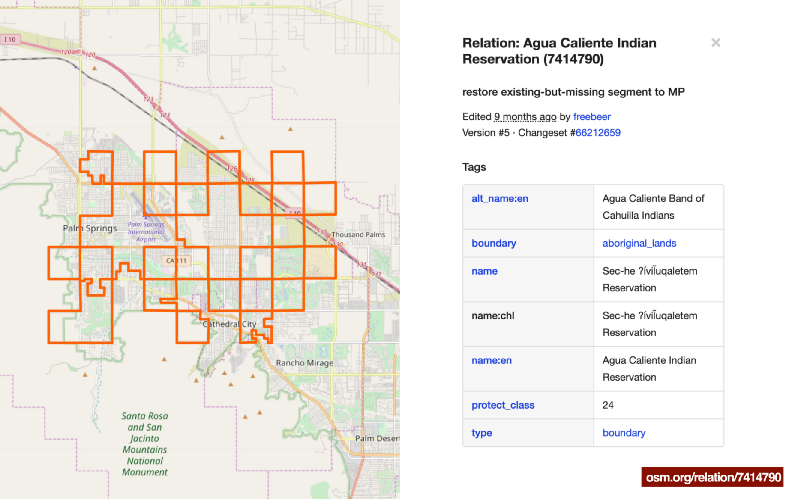

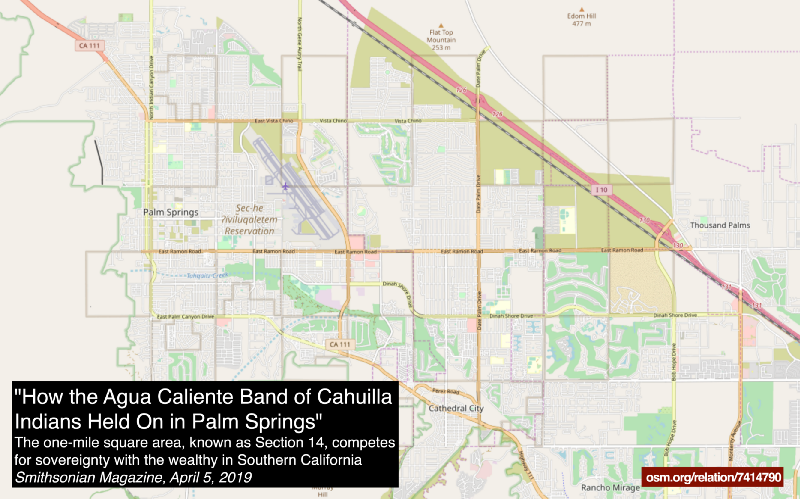

Things get even more complicated in some areas. This is the Agua Caliente reservation in Palm Springs, California. It’s also left off of a lot of print maps. And you can see it’s one of these patchwork areas when the US government was giving out land to the railroads, and in this case they gave (back) all these other parcels to create this native reservation. And that became extremely valuable land. For any of you who are in the Washington DC area in the next few months, there’s a really great exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian that’s specifically about this reservation and the decades-long legal fights from these native people trying to not be forced off their own land.

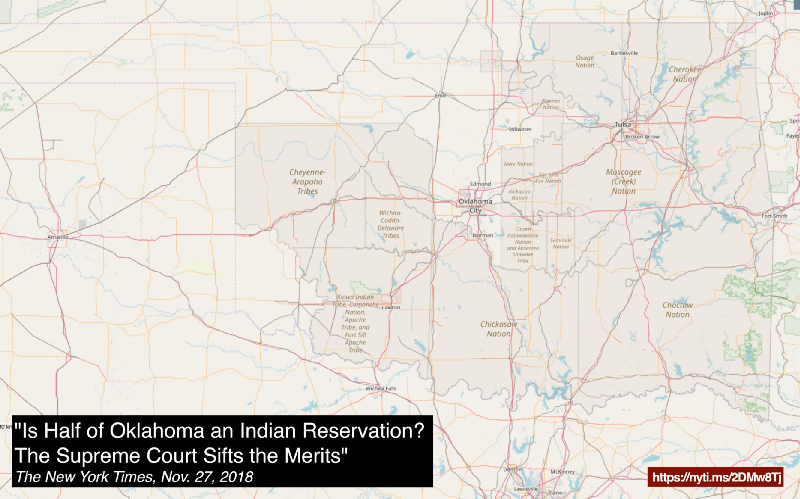

And OpenStreetMap now shows that actually more than half of Oklahoma is still technically made up of Indian reservations. And there’s an ongoing case at the Supreme Court. What is going to happen, we’ll see.

So that’s where we are now. We now see these native reservations on the map, although there are a lot more that we still need to include in the database. And we also need to do more research and discussion to figure out what other tags we might need to introduce to describe native trust lands or other sub-categories of reservations.

What you can do: find out the native land that you live on (native-land.ca is great for that). Find out what the treaties are in the area where you live. Check to see if the reservations around you are included in OSM.

Finally, I hope I’ve given you a bit of a sense of what it would be like if you see other things you’d like to add to OpenStreetMap, and how you might go about that. Don’t be afraid to propose new features, or to make pull requests on the map style!

Thanks to everyone in OpenStreetMap who did a lot of work to get this process started and to help carry it through to the end.

For more readings about native treaties, I recommend:

- From Vox: “6 Native leaders on what it would look like if the US kept its promises”

- From Indian Country Today: “If you don’t know treaties and sovereignty, you don’t know history”