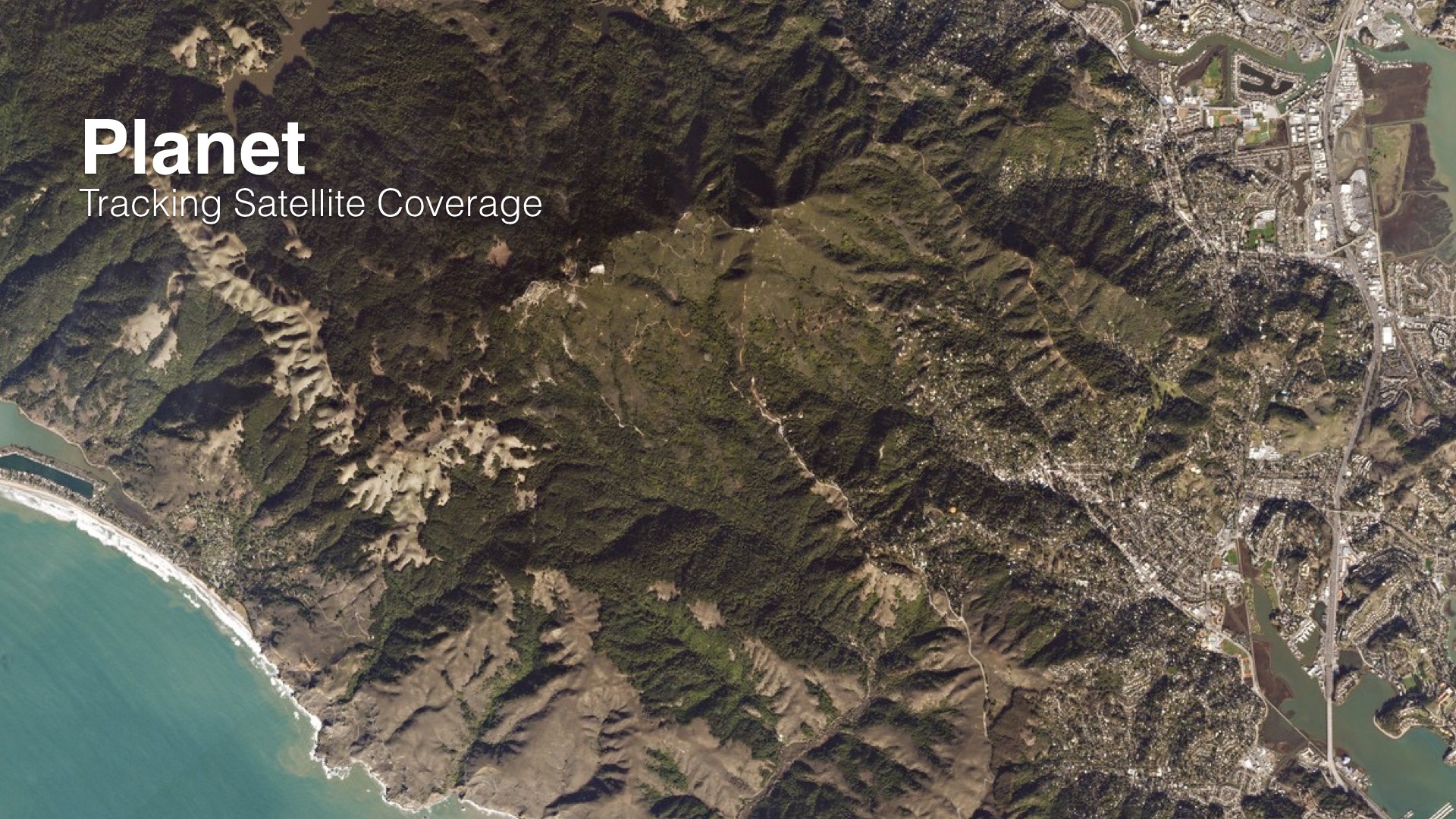

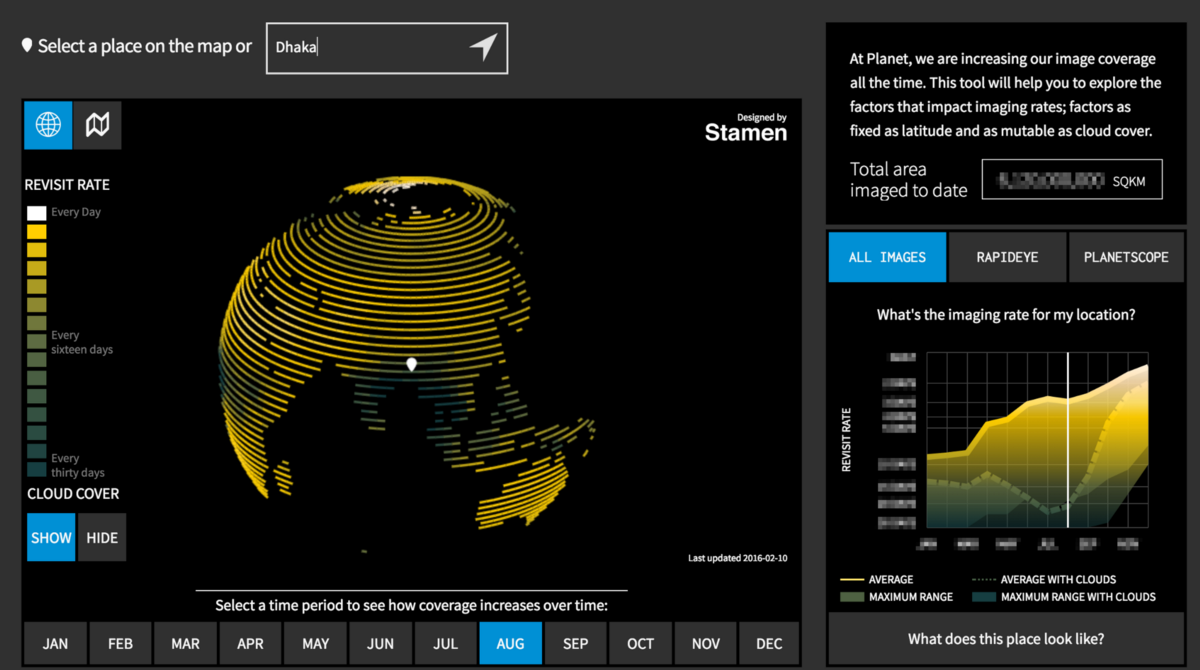

Earlier this year Robbie Schingler, co-founder of Planet, asked Stamen to design and build a presentation that showed:

- Which spots on the globe Planet has daily or near-daily coverage of

- How this daily coverage changes during the year, due to weather and satellite deployment

- What progress Planet has made and is making towards its mission to provide a daily picture of the entire, well, planet

So we did!

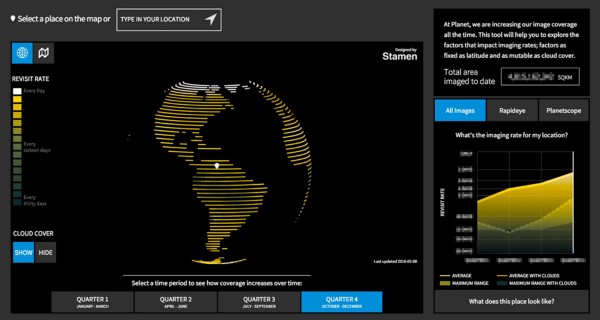

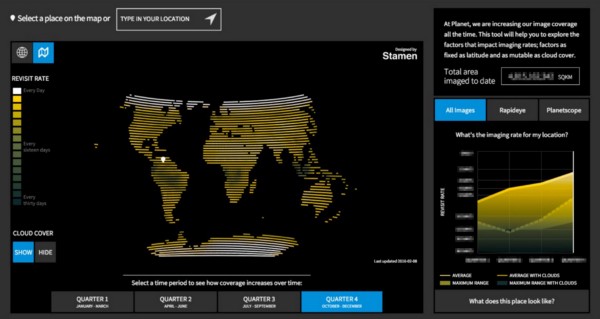

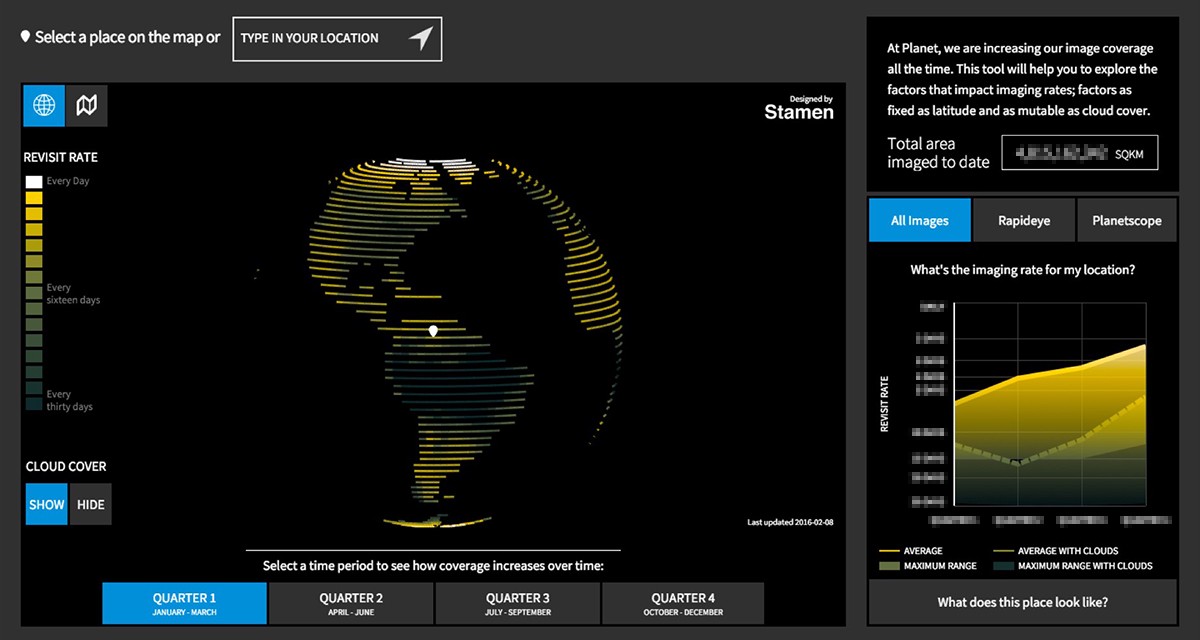

In the examples below (which uses historical sample data), bright is good (coverage very often), and dark is bad (coverage not so often) and of course, forecasts are subject to dependancies with launch schedules:

There are a number of reasons why a global daily picture of the planet is trickier than it might seem at first (in addition to being, you know, totally awesome). The first is complex. To see why, take a look at this animation of predicted Planet satellite locations on August 31, 2016. The orbital data to create the visualization was collected from Dr. T.S Kelso’s Celestrak.

Planet’s satellites are released in “Flocks”. The individual satellites in each Flock have a similar orbital path that drifts over time. Two satellites on the same orbit, but at different positions in their orbit, will pass over different areas due to the Earth’s rotation. But notice that even with the many satellites plotted above, there are vast areas without any coverage at a given time.

Besides simply having enough satellites, another challenge is putting up satellites with high inclination. This is the angle of the orbit makes with the plane which passes through the Earth’s equator. The inclination determines both the maximum and minimum latitude a satellite will reach during its orbit. Flock 1C and 2P are both in polar orbits, meaning they have large inclinations and will pass over both Antarctica and the Arctic Circle.

The second is a lot simpler: clouds! It turns out the world is a very cloudy place, and while Google Maps has conditioned us to think that we can look at any place on the planet and see the ground, they in fact do a tremendous amount of work to strip out all the clouds that block satellites‘ views. And Planet’s in the business of supplying data and pictures of things on the ground, so while images of clouds are cool, they don’t consider a place properly imaged unless you can see the ground clearly (and do alot of work to make this happen).

The cool thing about this, from the point of view of people who like to tell stories with data, is that you can start to see things about the world that you might not have been specifically looking for (which is one of the reasons that what Planet does is so amazing). Planet’s improving their coverage all the time and sending more and more Doves into orbit, so makes sense that if we look at this data over time, more and more of the planet would be regularly photographed. In this image, there’s a deep dark band across India and Southeast Asia, and in the chart you can see a corresponding drop in the effective revisit rate during July and August. Monsoon!

We’re getting more and more focused on projects involving satellites and imagery from space, so if you’re interested in this kind of thing, we’d love to hear from you.

Have a good day, space fans!