CaliParks.org opens a door and listens to people being themselves outside

This spring, CaliParks.org (a site I worked on with GreenInfo when I was still at Stamen Design) relaunched with a new look and a clear purpose: Highlight the thousands of photos pouring out of California’s parks every day.

And it’s working amazingly well. I did a survey of 100 parks on the site on a recent Saturday, and here’s what that looks like in a three-minute video slideshow:

As with any new web thing, there are many more features one might want or dream up, but at this point I’m reflecting more on how we got here and what it means to have a daily crowd-sourced view of each of our state’s nearly 12,000 public parks.

CaliParks.org originally launched, in a different format, in February 2015 based on work by Stamen Design, GreenInfo Network (where I’m now executive director), and Hipcamp.com, with funding from Resources Legacy Fund. The project was among a handful of “skunkworks” experiments sponsored by the Parks Forward commission, which was charged with charting the future of California’s state parks.

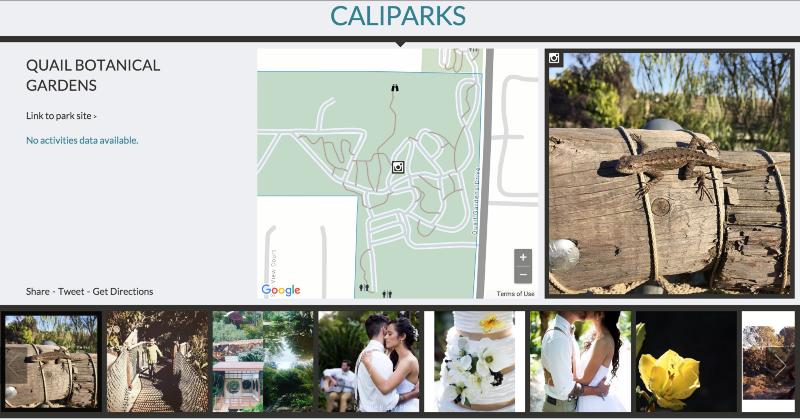

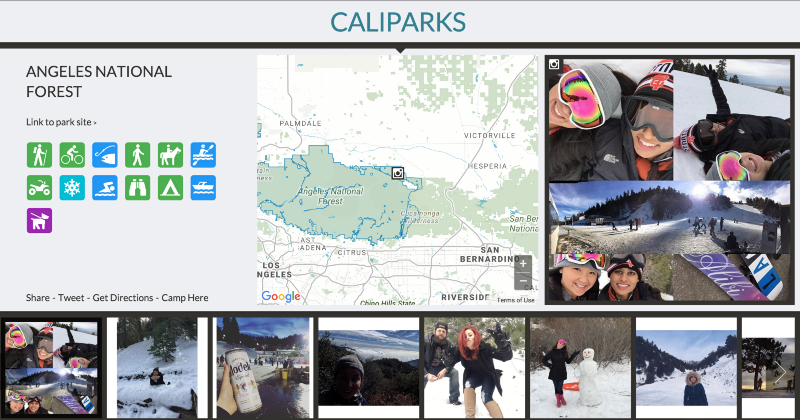

The goal of the site was pretty simple: Create a search engine that people could use to find a park near them, anywhere in the state and regardless of which agency owned or managed that park. We wanted to show not only where the parks are, but also what people are doing in them. There are nearly 12,000 parks in the state. Social media is the only place to get the kind of view we wanted.

In that context, the site is actually rather radical: Take a definitive dataset of California’s parks (calands.org, more on that below) and mash it up with social media with zero curation.

That last part is the key: Unfiltered social media. This was a leap of faith and one that most in the parks community, frankly, would run away from. Agencies can’t take the risk of illegal activities showing up on their sites, and they don’t want to take the risk of even unsavory or undesirable images.

With an independent and experimental project, we were able to take that risk. And we had to: Thousands of images get posted daily, so curation is just not possible.

Some offensive images get through. I did the 100 park survey in the video above after a friend reported an exceedingly offensive image posted within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. It was a doctored “meme” image — not real but still disturbing. It violated Instagram’s policy on offensive images, we reported it using the link on every Instagram photo page, and it was gone the next day.

But I wondered: How often would I find such things posted from inside California’s parks?

The answer: out of 100 parks, I saw only that one single offensive image. Compared to hundreds of beautiful, heartening, funny images of people and parks and, yes, a fair number of boring selfies. Even those selfies have a cumulative impact that really puts the public in public land.

So the risk of uncurated social media is paying off and I think it will pay off even more over time. As it turns out, regular people mostly find friendship, community, beauty, and delight in their parks. And that’s mostly what they share.

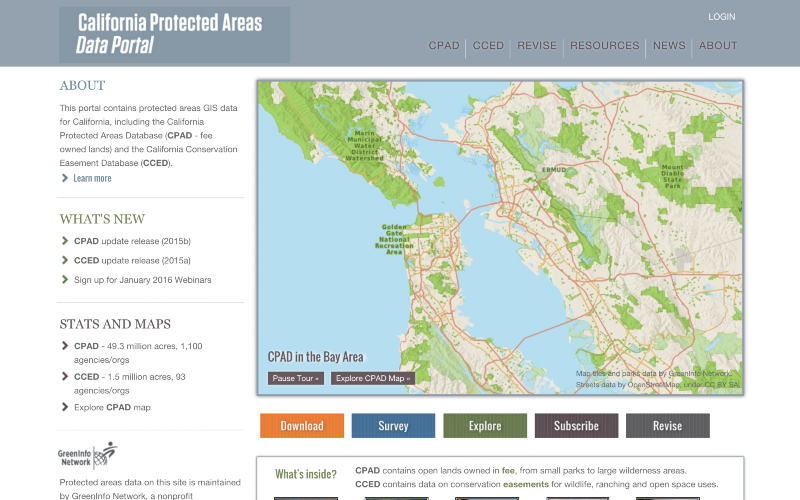

For me, the roots of the work go all the way back to 2009 or early 2010. I was editor of Bay Nature magazine and running their website, and we developed an idea for a Trailfinder to showcase outdoor experiences in the Bay Area. As part of that, we used parks data from the California Protected Areas Database, an incredibly rich and important resource developed and maintained by GreenInfo. None of these projects would be possible without CPAD’s complete inventory of parklands, with accurate names, boundaries, and links to managing agencies.

We took that parks data and cross-walked it with “Places” on iNaturalist.org to get lists of recent nature observations and then we also pulled in Flickr photos by querying park names in photo tags.

The project was only partially successful, but the core insight was revelatory: People are already sharing their experiences in parks. How can we listen and amplify those stories?

In early 2013, still at Bay Nature, I began collaborating with Jon Christensen (then at Stanford, now at UCLA) and Eric Rodenbeck (CEO of Stamen Design) on a proposal for a much more ambitious effort to harvest social media based on geolocation from many more platforms. Soon after, I became Project Director at Stamen and Jon secured resources to design and build the first effort, under the leadership of George Oates, Stamen’s art director at the time.

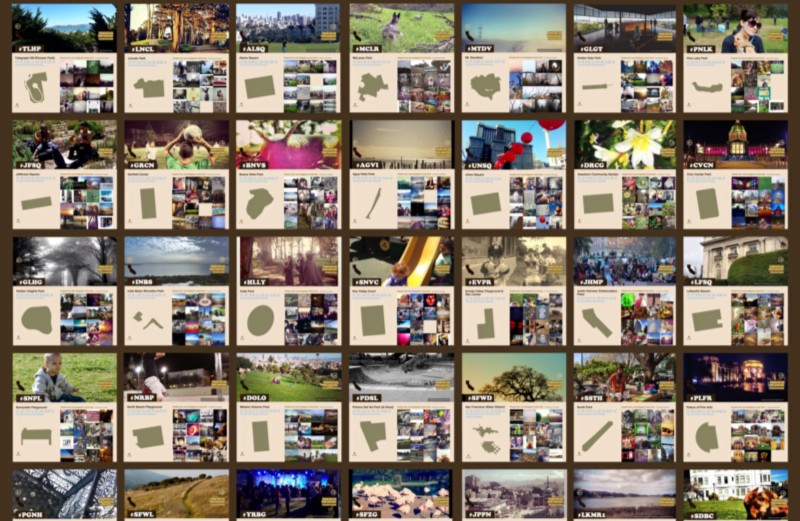

Here’s a mosaic of pages from that first site:

This was a really important learning experience. We learned that the Wander button is awesome (a different random park on each click). But we also learned that Tweets in parks are almost never about parks, Foursquare is hard to manage, and Flickr gives mostly traditional nature photos.

And we learned that Instagram swamps it all. Just tons of image, all the time.

Even so, when we built the first version of CaliParks.org, we pulled our punches on Instagram. The images coming from Flickr seemed more like the “outdoors photos” we’re used to seeing in magazines and on park agency websites. We put those at the top of every park page and ran Instagram in a smaller strip further down, hedging our bets.

In hindsight, that was the wrong call. After watching the feed for a few months, it was clear that Instagram is where the life is. So last summer, we started designing a new version at Stamen, and we went all in on Instagram. That’s what’s just launched.

Still no curation, and it’s just a joy to use, to visit and revisit to see what’s new both at parks I love and at random parks I’ve never heard of. People are mostly just people in parks having wonderful experiences together. Not only does it give me faith in support for public land, but it also affirms my faith in people and social media.

So much of the web is the domain of extremes, of outliers and petty bickering.

CaliParks opens a door and just listens to people being themselves outside. Sure there are going to be a few drunks, some creeps and vandals. But most times when I hit that Wander button, I’m charmed and delighted.

Because for the most part our parks and the people in them are joyful, beautiful, and alive.