Greetings from Berlin. Earlier this week I was in Turkey, where I’d spent the last week coordinating the install of our curation, Mapmaker Manifesto.

The second Istanbul Design Biennial opened to the public on November 1. Produced by iKSV, one of Istanbul’s, if not Turkey’s, largest arts foundations, the event worked with over 50 artists, designers and artist/designers who each produced a manifesto under the timely theme of The Future is Not What it Used to Be.

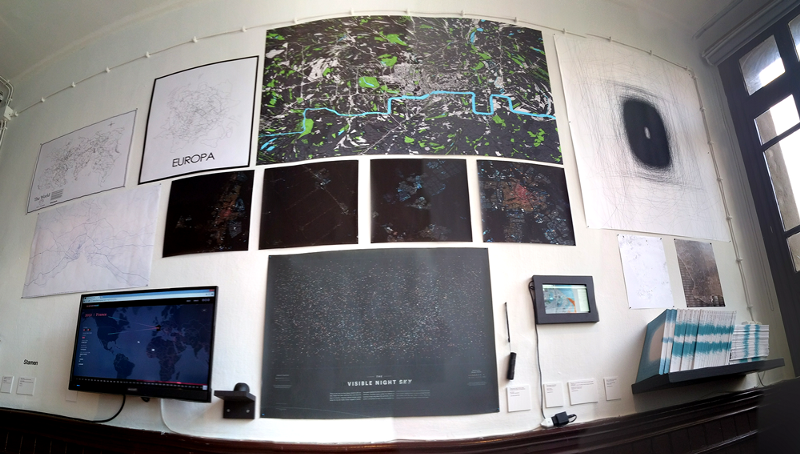

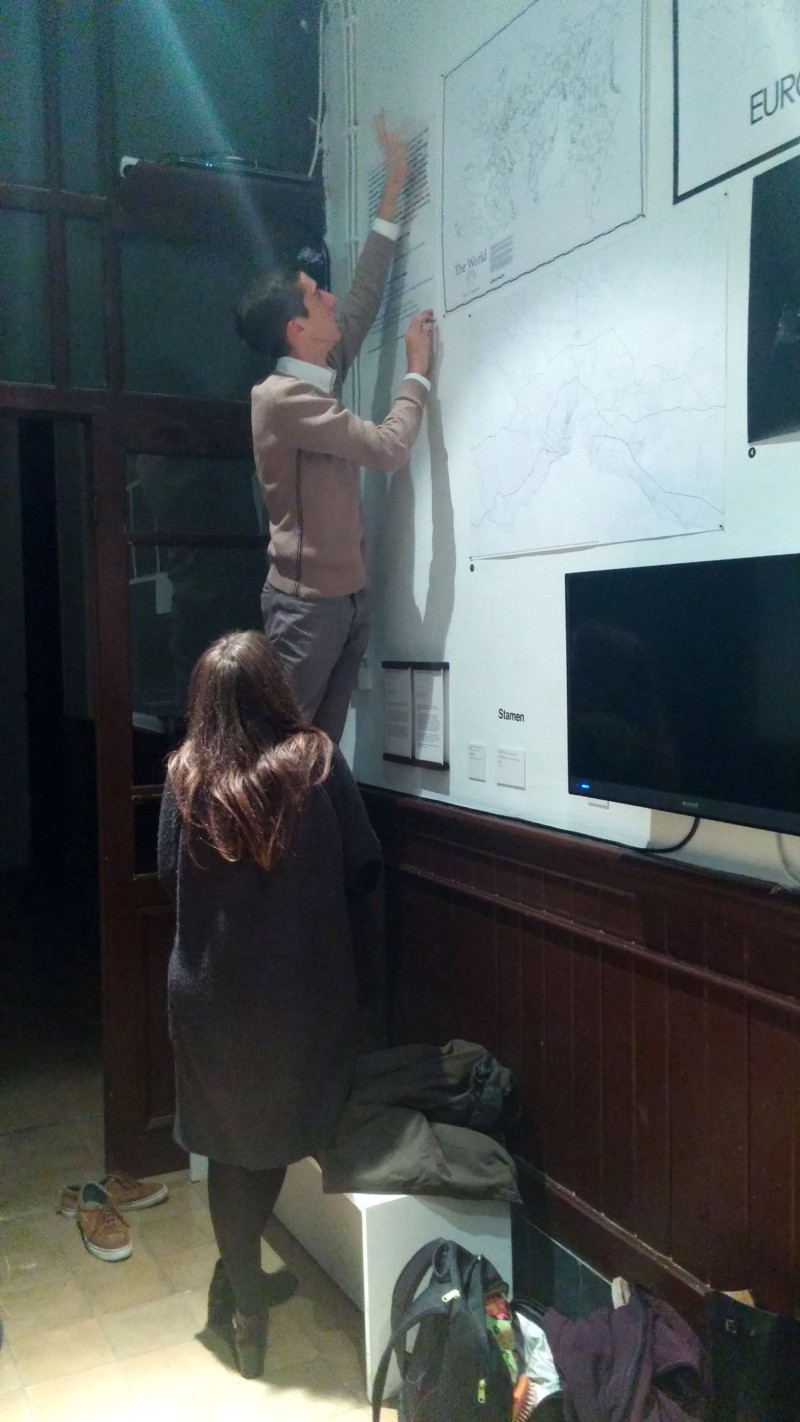

The room for our curation within a curation in is a funny, narrow one, with paneling up to my ribcage topped by nearly 17’x12′ of white wall on either side. The other two walls are home to a large window overlooking an abandoned building on one side and the entry way (with another window looking into the room) on the other.

The room has received an overwhelmingly positive response from curators, mapmakers, designers and artists who have visited it (as well as a mention in Design Boom, featuring The Refugee Project by Ekene Ijeoma and Hyperact.) I had multiple people tell me that it was their favorite room in the entire exhibition, even though the installation was not complete for opening weekend. The manifesto itself was not installed until Sunday evening, and the website (which is the guide to the room) is being added this week.

Designing inherently comes with a healthy dose of perfectionism, of course the incompletion caused me anxiety and stress. But then I remembered that manifestos (and exhibitions, for that matter) are idealistic in nature and messy in practice. The Mapmaker Manifesto is no exception. The manifesto calls for maps of all kinds as a kind of data collection process, to see if there is any universality that reveals itself through multiple representations of You Are Here. Data will save the world, right? If we can just see the things that are wrong, then we’ll fix them, of course. We’ll make a future together, if we can just agree on what the map says.

Of course, we know this isn’t true. As Becky Cooper points out in Mapping Manhattan (which was included in the exhibition) maps are by no means objective, and in fact the contrary is true. Not only are maps subjective, they can sometimes be downright wrong. The false location of the Greek School (the Biennial site) in Google Maps reminded many of us foreigners of this fact. Joseph Dana from Monocletook out the pen and paper to route the actual location of another site for one of his colleagues, warning her against using the tool.

We call out the subjectivity of maps in our curation, which is, in and of itself, a very subjective map of maps. I had the great pleasure of speaking about this during a Designers in Dialogue session with Helen Maria Nugent, moderated by SAIC student and curatorial assistant Denise Bennett. Helen’s project maps the look of love using eye tracking technology, and then manifests them as objects made with the materials of anniversaries, such as paper and silver. Denise paired us together so that we could talk about the expansiveness of mapmaking and types of maps.

The biennial itself had countless maps hidden inside of it. I did my best to hunt for them all. Here is one about the 6th extinction, byAlexandra Daisy Ginsberg:

And another one from Repair Society:

And another one from Occupy Gezi Architecture:

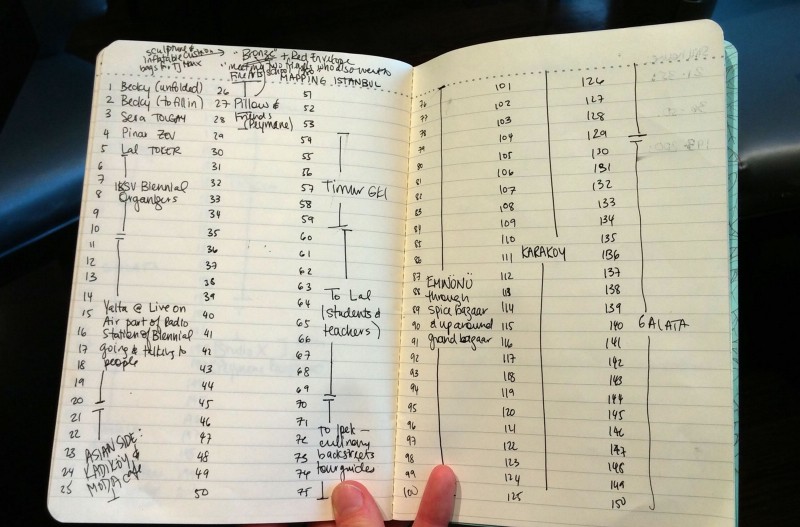

While I was busy talking about maps and tending to the still-in-construction room, Becky Cooper was on a mission throughout Istanbul. As part of the Mapmaker Manifesto, Becky walked the city with a translator, and documenter, and a whole lot of maps for her Mapping Istanbul project. This project, along with our online curation, will be happening throughout the Biennial, and perhaps beyond it. During her walks, she spoke with over 100 people, and even helped a blind man to map his memories as she described them to her. The hope is to collect enough of these maps and stories to make another book.

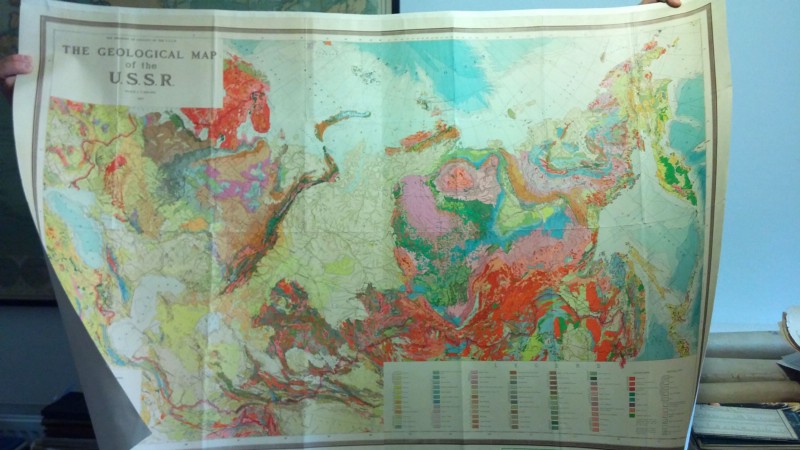

One of the most exciting diversions was seeing the map collection of iKSV’s editorial manager, Kerim Bayer. Over the past 7 years, he has been collecting maps, most of them from 1850–1950. During a break, we rode his motorcycle up to the top of one of Istanbul’s many hills to his office, where he has nearly 1000 maps! Here is a small sampling:

Kerim is an aspiring mapmaker himself. In speaking with him, it seems there are very few mapmakers in Istanbul (or at least few that he knows). He also pointed out that the OpenStreetMap data in the area is sparse, making it hard to work with. My hope is to keep in touch with him, and perhaps there is an opportunity for a Maptime in Istanbul, with enough people. Design is beginning to take off in Istanbul, and perhaps a community of map designers and data visualizers will come with that shift.

Things change all the time, of course, but there was an overwhelming sense among many of the artists and designers present that we are at an apex of sorts. Istanbul itself exists in a brackish water between old and new. Perhaps this has always been the case in a city that spans two continents, has had multiple names, and carries with it the weight of thousands of years of history. Taking over an old Greek school with futurist design ideas seemed in and of itself fitting for this year’s Biennial. The future-facing works within the exhibition created a brackish water of its own between art and design, modernism and postmodernism, science fiction and science fact. It can be quite overwhelming.

Our little room of maps captures this feeling, and like everything else in the exhibition, will before we know it be gone. The documentation, including the maps themselves, will be all that remain.

**

Visit the Mapmaker Manifesto site and see more photos on Flickr