Here at Stamen, we’ve been doing more works for and about parks, first our map for the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy and then our own parks and social media experiment at parks.stamen.com.

We love parks!

I especially love parks. I spent almost a decade telling stories of local parks and wildlife for Bay Nature Institute, and toward the end of my time there I was constantly trying to push the envelope of what a small nonprofit could do with technology.

Now that I’m at Stamen I’ve got a slightly different view of how park agencies and nonprofits can and should engage with technology.

Back at Bay Nature, I thought, “I’ll figure out precisely what we want and do all the research, and then I’ll just hire someone to make that exact thing!”

I’ve now seen this same thought process at work in a few RFPs for mobile websites and interactive maps for parks and trails. Figure out every possible feature you and your colleagues might want, put them in a giant list, throw in some house-made wireframes, and then send out the RFP for precisely what you know you need.

Makes perfect sense. Except:

It doesn’t work.

What you think you know at the beginning of the process may well turn out to be dead wrong, and, more importantly, you lose so much of the big win of hiring professional designers when you try to solve all the design problems ahead of time.

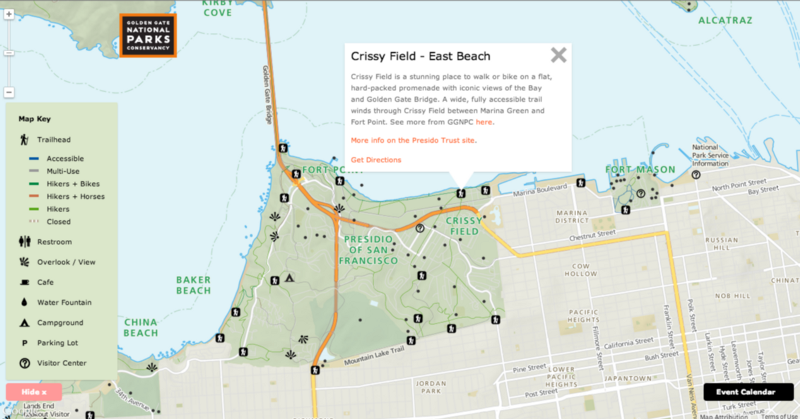

When Stamen took on the effort to redesign the maps of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, we were fortunate to have flexible, and all-around awesome, project leads at the Conservancy. Michael Norelli and Mason Cummings were ready and willing to hear that the enormous feature set they’d assembled was too big to do well in one scope of work.

Instead, we focused on the key goal: Get people to the parks.

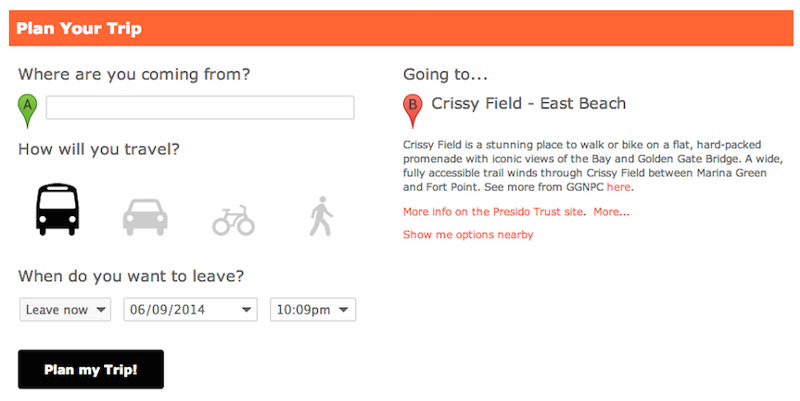

Being able to focus that way was incredibly important to making sure the effort was successful. It meant the Trip Planner was the most important thing to build out fully, complete with bespoke directions to obscure locations and special warnings if parking at Muir Woods was impossible.

We made some awesome Trail Views (and those weren’t in the RFP), but the key to success here was understanding that getting people to the parks was the top priority and the main measure of success.

What about the original RFP’s several other pages of requirements, from hawk tracking to editable management zones? We had to let those go for future phases of work. If we’d tried to do them all, we wouldn’t have finished anything well. Check out the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy’s open source code repository if you want to do a deep dive into the code that made that project possible.

Better Scoping Principles

- Prioritize: define must-haves, then cut your list in half

- Start simple, move quickly

- Release early, release often

- Be ready to change your priorities

- Favor open data, standard formats, and existing tools

- Prioritize? YES!

Avoid letting data management dictate design

A common thread in parks and mapping RFPs is that data pipelines, GIS workflows, and general data management sometimes receive a lot more attention than the ultimate goal, which is usually something like getting people to parks or helping people discover new trails or find programs in parks.

That’s natural, since the people writing the RFPs are the ones who most often wrangle all that data. But unless you’re really doing a pure infrastructure project, resist the temptation to let data management and your internal needs dictate the thing you’re getting built.

Which leads to:

Use the kinds of software you aim to hire someone to build!

This might seem obvious, but it’s surprisingly rare, especially if you’re a longtime parks pro. Hey, you already know tons of trails and parks and birds and nature lore, why do you need to use an app or website?

Well, first, you might discover some things you don’t know or new ways of looking at things you do know. But more importantly: Just trying out existing tools and really using them is a huge source of insight. Heck, you might discover something that works so well that you want to just hire the people who built it to make a special version for your park or agency.

Keep it simple! (That is hard.)

You might notice that the best existing services and applications are often the simplest. Whether through dumb luck or, more likely, previous mistakes combined with persistence, they’ve figured out what people want most and they’ve given it to them. And they’ve made it easy.

You can do the same in your search for a technology firm to build your stuff: Keep it simple. Favor qualifications and past work over ability to navigate complex documents and matrices. Find a firm with which you can have a relationship based on collaboration and trust. Hire them, take some risks, be ready for small failures in the service of big wins. And have fun.