Eric Rodenbeck (ER): Welcome, Alex! I’m excited to talk with you today and showcase you and your work. Let’s start with how you came to be at Stamen. How did we find you? How did you find us? Why are you working here?

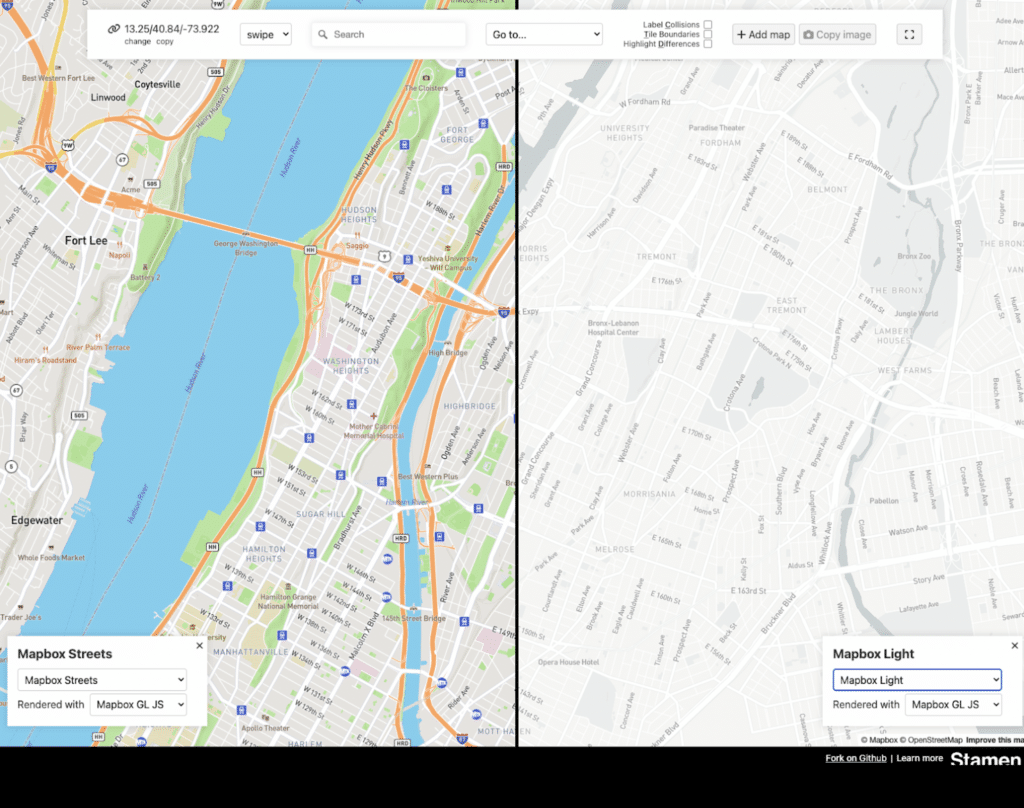

Alex Parlato (AP): That’s a good question. Well, I had been working at Mapbox for five years and I was hoping to try some new things. I wanted to get closer to design without going back to being a designer. I went to school for design and designed for a time in my career. I moved into software development work and feel most comfortable there. I like being in an organization that values design. It allows me to take part in design without being a designer. When I saw my Mapbox co-worker, Kelsey Taylor, come over to Stamen I thought, “That place looks great!”

ER: That’s interesting. You’re a designer who became a software developer. Is that common?

AP: It is common. Around the time that I was getting out of school, it felt like the industry expected designers to have developer skills. It seems that it might be going away from that direction now. With tools like Figma and some of the AI tools out there, designers need fewer code-writing skills than a few years ago. But for a while there, a lot of designers had to write code and a handful of them, like myself, pursued that direction.

ER: You’re right. That question about whether designers need to learn code right now is worth asking. Other designers at Stamen have felt the need to crack open the cartographic tools and learn to code so they could do the work. It sounds like you felt something similar. You felt like you needed a solid understanding of the internet’s affordances. And we’ve gotten to a point where those affordances are very well known due to the ubiquity of the web.

AP: It’s interesting because the tools have expanded. I’ve definitely worked on many custom tools here at Stamen and at Mapbox where we tried to support designers by making tools where they wouldn’t need to learn to code. But there are also some other decisions you might want to make that those editors can’t serve. That’s where you need to get more technical and that can be a blocker for designers. My hope is that tooling gets designers where they need to go. I never want to prevent a designer from learning code or expanding their skillset. But I want designers to have the widest possible toolbox and I look at my role as someone who builds those tools. Designers already work within limitations. I think about how I can remove barriers within the tooling itself.

ER: I’m curious to hear your thoughts on what the work is like. You have a unique perspective in the sense that you’re trained as a designer and now you’re coding stuff. Stamen, to me, is a very deliberate blend of those disciplines. Do you think that there are skill sets and problems that kind of translate across both of those?

AP: Yeah, definitely. It depends on the project in which I get to fulfill those roles. In the dataviz realm, you work with large amounts of data. You use or write tools to see what it looks like and experiment with it. I love to think about different ways to bridge the gap between the technical and design-oriented sides of it. Stamen is definitely at that intersection.

ER: And you carry that here at Stamen with your role as a Design Technologist. I describe that role as someone who can make stuff with code and who cares about how things look. Is that how you think about it?

AP: In terms of role definition, that describes me, but it doesn’t fully describe what I do on a given project. As far as I know, AI will likely change how code is written in the next five years. My job will have to change. But there are more soft skills involved. I can learn new things or needs from the client. I can communicate a certain way with them to come to an understanding. I can translate that to the medium, whether it be design, coding, or whatever tools we’ll have in the next five to years. I don’t have to attach to a hard-defined role on paper. That doesn’t mean I can’t have a defined role on a project based on my skill set.

ER: I think that’s one of the secrets to Stamen’s longevity—23 years now! We pivot constantly, focusing on the forward edge of design and tech as a way to stay relevant in the market. And that’s that’s much different than committing to a specific tool set or a specific industry.

Speaking of pivoting, you’re also a teacher, right? Where are you teaching?

AP: Right now, I’m not teaching. I was teaching at Maryland Institute College of Art, where I went to school.

ER: I love this about our team too: so many of us are teachers. I’ve taught at California College of the Arts, Eric Brelsford teaches at Columbia, Alan McConchie is one of the founders of MapTime and taught at the University of British Columbia, and Kelsey Taylor led a collaboration between National Geographic and Adobe around online storytelling.

AP: It’s definitely a different skill set. I don’t have a ton of teaching experience. But yeah, it’s interesting. I have mixed feelings about teaching. Sometimes I enjoy doing the work over teaching it. It also matters how engaged your students are. I enjoy students that aren’t afraid to take risks and experiment with projects. But many folks—students and non-students alike—have grown fearful in that area. Maybe it’s the pandemic, but it seems like people have become paralyzed with fear. People are too precious with their work and don’t take the chance to experiment and fail.

ER: Even in my sketchbooks, the first try is never the thing that you’re done with. I always hate the first thing that I’ve made. I’ve learned to keep working until I don’t care quite as much and I’m not so paralyzed. Then I can start to turn out some stuff that I’m happy with.

AP: I’m definitely the same way. I’m trying to get back into my art grind. I was regimented about it for many years: every Sunday, all day long, I would be in my studio painting. It taught me to not be too precious with my art. Just go in there and do work. “Doing” over “thinking” is always the answer for me. It’s easy to become paralyzed by your input/output ratio. It’s another real problem in the internet age.

What I mean by that is limiting your input of inspiration and making sure you produce something. If your production is lagging behind what you’re taking in, then you become paralyzed. It becomes overwhelming. You can see every possible kind of painting on Instagram and not feel able to produce anything. But if I’ve had a normal amount of exposure, I have some inspiration and I’m not paralyzed by what to do.

ER: Do you think that’s true for your work at Stamen as well? I’m thinking about writing and discovery as part of production work.

AP: I’ve been more focused on some map-tooling infrastructure. That requires different creativity than what we were talking about. I haven’t participated in as many open-ended projects that call for that kind of discovery.

ER: Over time, the projects and people at Stamen change. And the people’s roles within those projects change. I appreciate you being here. You bring your unique perspective to those projects! Thanks for talking with me about all this stuff.

AP: Agreed, thanks! It’s always fun to talk about these things.