Cartography is a powerful tool for understanding the world and our place within it, but sometimes maps conceal more than they reveal. Throughout much of the history of cartography, maps have been used to forcibly claim territory and exploit the land, erasing the histories and claims of the people who lived there before. Native Land Digital is a new organization with the mission “to map Indigenous lands in a way that changes, challenges, and improves the way people see history and the present day.” In this episode we talk with Tanya Ruka, a Māori indigenous multimedia artist and designer who is the new Executive Director of Native Land Digital, about acknowledging the land we live on, how to map uncertainty, and the role indigenous knowledge plays in the fight against climate change.

As a multimedia artist, Tanya explores the astronomical and seafaring practices of the Māori Master Navigators through photography, digital art, video, and public installations.

She also works with the Waitaha Executive Grandmothers Council to document and preserve oral stories and traditional knowledge of the Waitaha River as part of environmental protection claims. Through this work of mapping the traditional stories of the Waitaha River, Tanya integrates indigenous ways of knowing into western technological frameworks and colonial legal concepts of land ownership. These efforts led her to discover the Native Land Digital project, joining the organization originally as a researcher and now its Executive Director.

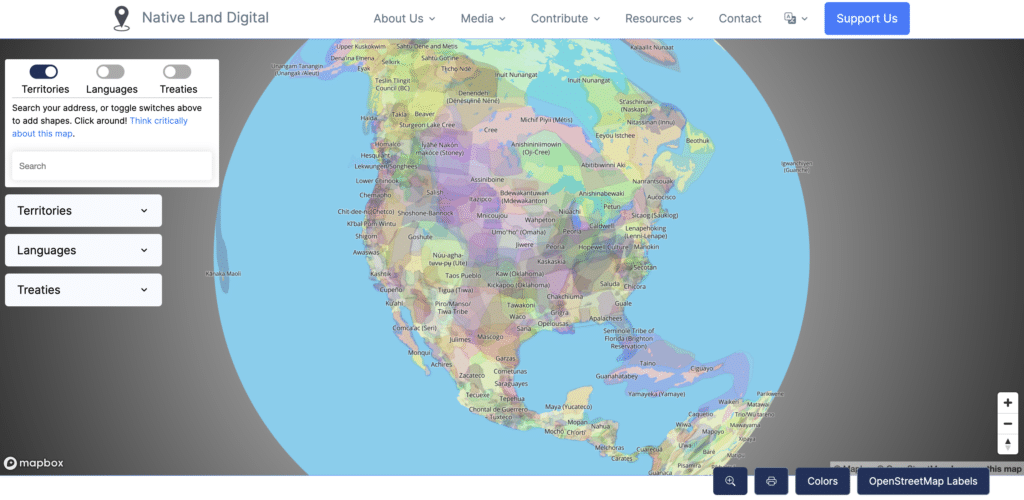

Created in 2015 by Victor Temprano, Native Land Digital is an interactive map of indigenous territories, treaty areas, and language groups, originally just for North America but later expanding worldwide. In 2018 the independent mapping project grew into a non-profit organization overseen by a board of directors made up of indigenous people from nations around the globe.

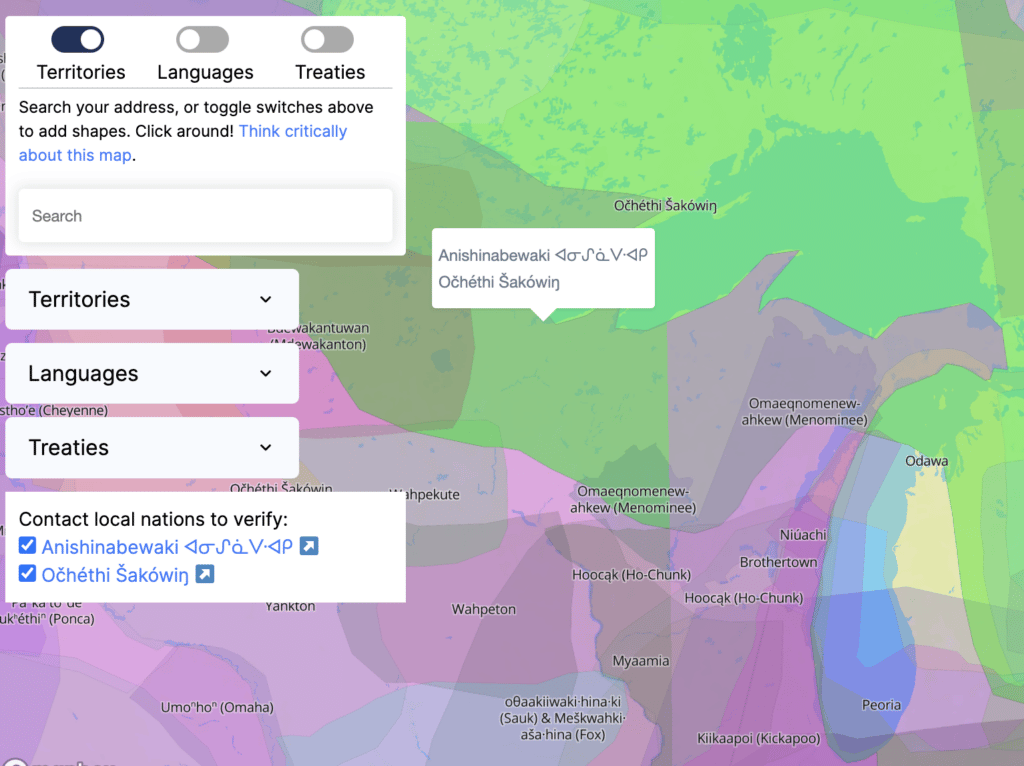

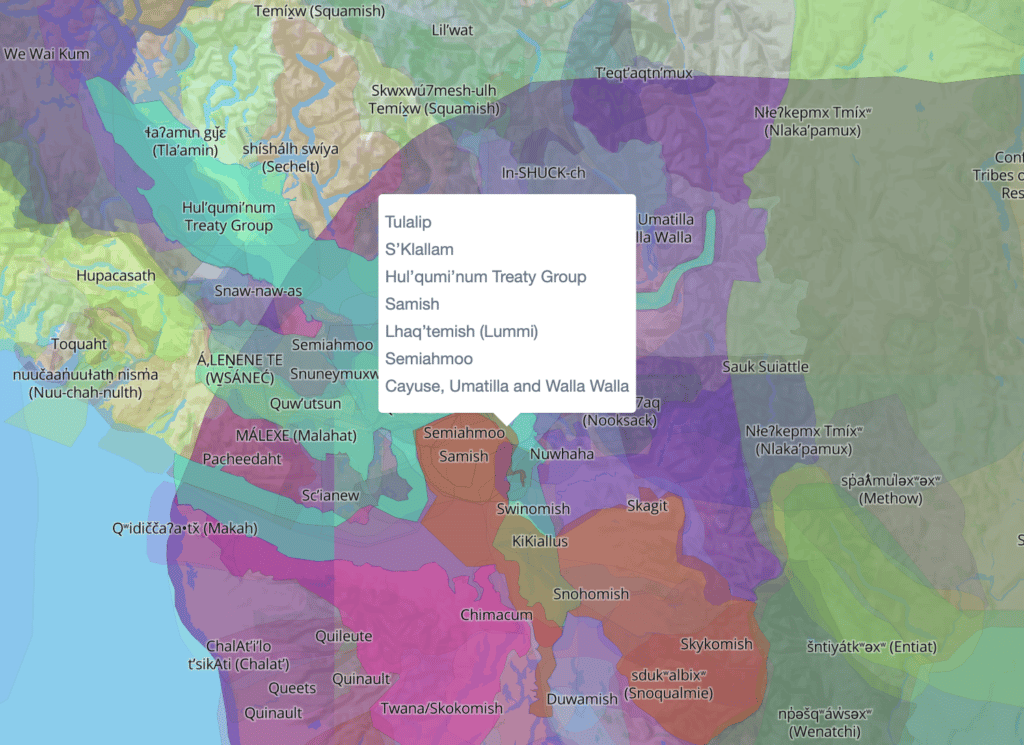

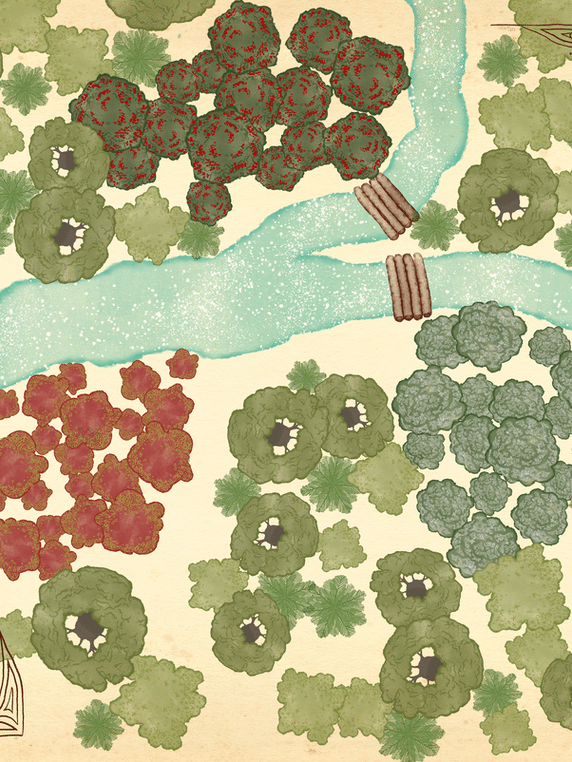

When visiting the website, users see a map that looks very different from the ubiquitous political maps that most of us are accustomed to seeing, with sharp boundaries between countries, states, and provinces. On the Native Land map, native territories are drawn with several overlapping semi-transparent polygons, representing multiple and complex conceptions of how people interact with land. The boundaries not only show places where people lived and settled, but also where they traveled for food and trade; they show where nations migrated or were forced to migrate over generations. This approach to mapping recognizes the uncertainty and complexity of how people relate to the land and strives to show a more organic and living conception of territory and cartography.

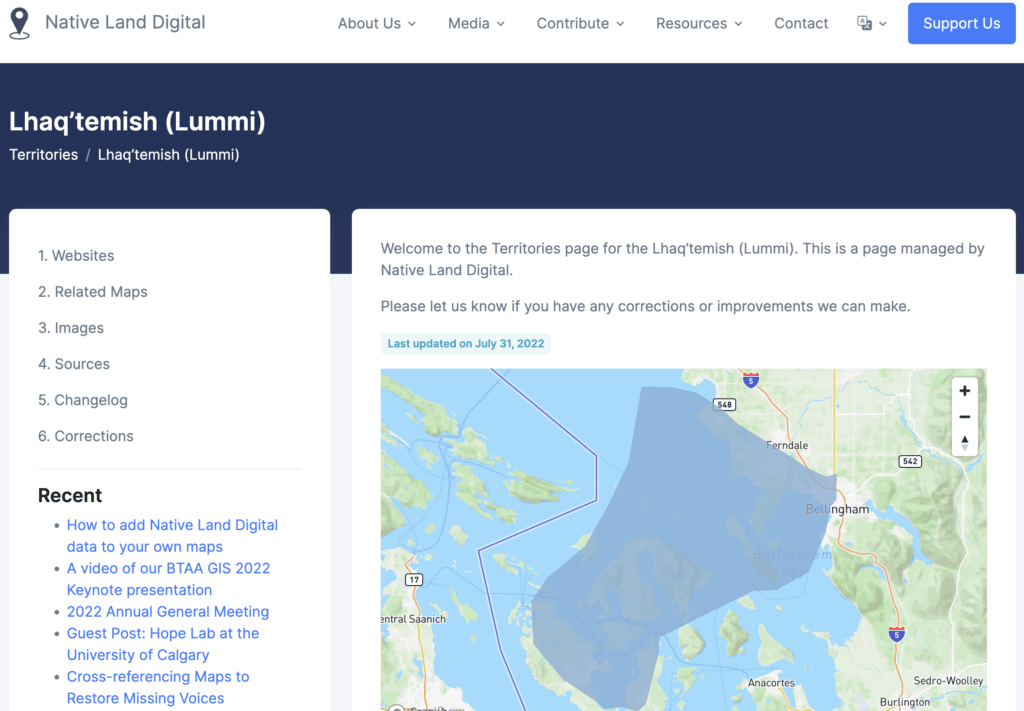

While interacting with the map, users can click on the map and see the names of the indigenous communities that live(d) in that place in the present or in the recent past. The map (and the rest of the Native Land website) is full of links leading to more information about these native groups, encouraging map readers to go deeper and continue learning.

Native Land Digital has ambitious plans to continue adding information to the site, pushing the boundaries of cartography to make the map feel more organic and alive. They plan to add more functionality to the site to enable sharing of indigenous knowledge and practices and to support networking between indigenous groups. This sharing of traditional knowledge can help everyone find ways to live more sustainably and mitigate our impacts on the environment. This is all the more important given that indigenous communities are typically impacted more by climate change than non-indigenous ones. Tanya herself has many of her own projects underway with a similar focus, including research into traditional textile production using sustainable native plants and creating computer games (often with a map component) to share indigenous understandings of how ecosystems interact.

You can follow the work of Native Land Digital at their website (native-land.ca) or via their social media on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. You can also support the project financially on Patreon. To learn more about Tanya’s many artistic and research projects, visit her website at Fog & Moon Studio. And as always, tweet us your thoughts about this episode!

Transcript — +

[music]

You’re listening to Pollinate, a podcast on data, design, and the people that bring them to life, brought to you by Stamen Design.

Alan McConchie (AM): Whose land do we live on? How do we map uncertainty? What role does indigenous knowledge play in the fight against climate change? These are just a few of the topics that come up in today’s episode. I’m Alan McConchie, lead cartographer at Stamen Design, and today we’ll be talking about the important online mapping organization Native Land Digital with its new executive director and discussing how we can incorporate traditional native territories and indigenous ways of knowing into modern day cartography. Please welcome our guest.

Tany Ruka (TR): Kia ora tātou. My name is Tanya Te Miringa Te Rorarangi Ruka and I am Ngati Pakau Ngapuhi First Nations Māori from Aotearoa, New Zealand. Thanks for having me.

AM:Thank you for being here. Kia ora, Tanya. You have a fascinating background and I really hope we can get into who you are and how you came to your role and then we’ll talk about Native Land Digital in a little bit. But you’re a designer, an artist. You’ve shown in dozens of galleries and exhibitions using a fascinating variety of different media in your practice. Digital art, public art, multimedia, writing. You’re researching indigenous knowledge and environmental protection. There’s so many things that you seem like you’ve been involved with. And now cartography, too. So we’ll touch upon a lot of these things, I’m sure, but I’m sure people would love to hear you tell your own story of how you came to be where you are today.

TR: Sure. I think I should just first mention that everything I’m going to talk about today is from my perspective as a Māori indigenous person from Aotearoa, New Zealand. And all the background knowledge that I’ve gained is sort of from having conversations with other indigenous nations. But by no means is this a sort of general conversation that I can round up the questions and answer for everybody. So just want to make sure that everyone listening knows that it’s from my opinion and just from my learnings. So I guess if we look at that from a Mātauranga Māori perspective, Mātauranga Māori is our traditional knowledge, ancestral knowledge. So for me, if I think about how I came to be here today, it would be through generations, and I’m here from my ancestors. And our traditional oral stories, they go right back to the original atua. All Gods. And so these creation stories are what’s inspired my work. Because in order to be an artist, I have to go right back to the beginning because that’s what our tohunga – or I guess, the name is teachers – the wise people would have done. You start right back at the beginning when you’re learning. So that inspires my work. It also helps to ground me. It creates the framework for my living, myself, and my whānau. My family. So it’s super important to remember all those things even in our contemporary life. So my early years I was born away from my tribe. I was born in Australia. And then my mum and my aunties took us over to Europe. So my initial understanding of the world was not from my cultural background. It was from a multicultural background. We spent some years in Asia. And it wasn’t until I was 11 that we came back to Aotearoa when my mum’s parents were ill and getting older, so she wanted to come back and look after them. Which is what we do. As an indigenous people, we take care of our elders. So our ancestors and the histories, they were master navigators across the Pacific oceans. So I kind of feel like my beginnings were sort of like that. I grew up on airplane moving through countries and learning about other peoples and nations. I feel really lucky that that was my beginning. The three of them were nurses. So we weren’t wealthy. They just worked from country to country. Which I think would have been sort of what our ancestors did as well. They moved and then they would stay somewhere for a while, live, and then move again. Because we’re adventurers at heart. So, of course, navigation, maps, that’s in my blood. Long story short.

AM: Yeah. Absolutely. I think it’s really interesting to think– I mean, maybe I listen too much Carl Sagan or something. I mean, I love a lot of these kind of scientists who are thinking it’s inherent to humans to explore and wonder and journey. And it’s true for a lot of cultures. It’s not true for all of them. Certainly, Western Europeans like to think of themselves as the explorers, but there are so many other cultures that have exploring in their cultural DNA in completely different ways. And I think it’s really fascinating how that comes into some of your work. So you’ve used a lot of these concepts and it sounds like your sort of self-discovery of this heritage in some of your artwork. Is there any of those that are coming to mind right now that you’d like to share with us?

TR: I think because it is such– well, master navigators and that knowledge of mapping and traveling because our ancestors would have traveled tribaly. So there would have been a few family, or whānau, within the waka, the canoe, as it traveled. So they had to be clear on how to do this. And the knowledge behind navigational systems– because we weren’t using the European sort of– the [inaudible] and that sort of thing. They were using the stars. And so to memorize these star patterns across the sky, you would need to know the story of the star. So their way of thinking was a 360-degree view around the waka and the stars coming overhead. Aligning with the sunset, sunrise; the moon, what the moons doing; what the feel of the waka is doing. All those things are inspirational in themself. As an artist, you go from movement, to sound, to story, to visualizing these amazing stories for each star house. Because the star house has its own story, so it’s own generation. So I think today in our contemporary lives, we just don’t have to remember that much information because our phone will do it for us or our computer does it for us. So for me in the contemporary world, it’s quite difficult to even think of having those skills. And what’s inspired my art practice is trying to figure out and learn it piece by piece, word by word, story by story. And I know I don’t have enough lifetime left to learn these skills, so it’s going to keep me busy for the rest of my life and I love that. [laughter]

AM: Yeah. I think constant exploration, constant learning, is one of the things that for sure is inherent to being a human wherever we are, whatever culture we come from. And also, one thing that was really interesting, I was listening to– you gave a presentation at a keynote recently talking about your work protecting the Waitaha River. And that it really involved a lot of working within kind of Western legal constraints and colonial notions of ownership and territory. But the way you approached it was very interesting looking at what are the rights of this river and recognizing that there are parts of the natural world that are family to humans and are part of our family. And I’m wondering if you could tell a little about how you were working with that project. And I know that that led a little bit into working with GIS and maps as well.

TR: Yeah. I’m working with our Waitaha Executive Grandmothers Council. So that’s a tribal gathering of grandmothers. We are trying to use our treaty claims, the contemporary versions, I guess, for environmental issues. So for our river in the South Island, there was an issue because they wanted to put a hydro dam on the river. A lot of factions, not just us, the mountain climbers, the whitewater rafters, they understand the full beauty of this river and how it comes down from the southern mountains. Just it has an energy of its own. You don’t mess with that. So for Māori, we understand the land as an ancestor. And our respect is given to the land because we understand that we are the younger in that relationship. The land is the elder. The tuākana. So we have to give respect to the land. And for us, with mapping, there’s this idea that you’re mapping boundaries, you’re mapping resources and property and money and what can this land give to you? But for us, the land is ancestor. And it’s body, and we feel that in our bodies because it’s part of our body. And that genealogy tracing back through the generations can trace us back to where we were related to the land. So it becomes very personal for indigenous folks. As I’m sure a lot of people know, that when we feel like our land is being tortured by extractive means that we get very upset and that’s when we’ll come together.

TR: And the idea of mapping sort of came in to try and figure out how we can do this but from a Mātauranga Māori perspective. So what does that look like? We’re actually mapping the data of stories. It’s not just about the land. Its story. So a grandmother’s story of how they used to gather food from the river. That’s data. That’s information. That’s mapping. Because she’ll tell you where that happened and who was born there and how many generations were there prior too. And then when you think about the amount of pollution that’s been generated around our rivers here in Aotearoa, agricultural pollution, I don’t know if your listeners have heard, but we can’t gather wild foods anymore from our rivers or our forests because there’s just too much pollution and it’s not safe. These are all moments or reasons to understand mapping from both our perspectives. And understand the Euro legal ways to do things so we can try and make our voices heard. Because when you’re looking at climate change, you’re looking at the potential for a lot of people to go hungry as our biodiversity is degenerated further. So it really just makes sense – it’s logical – that we should be looking after our biodiversity because that’s a free food source. I mean, for many countries around the world, the cost of living is increasing. And there are a lot of poor and middle-income people are becoming poorer as well because just everything is rising. So why not look after the biodiversity? Why not have an idea of what it is and then you’re feeding yourselves? So yeah, just figuring all that out is what I’ve been working on with our grandmothers and talking about to lawyers and governments and crowns.

AM: Well, yeah, and researchers are showing that native communities, indigenous communities are disproportionately already bearing the brunt of climate change. So this is yet another reason to make sure that these areas and these communities have the support and to survive and thrive. But this is knowledge that can help everyone. We shouldn’t assume that the only solutions to climate change are going to be technological ones or high-technological ones. Because in a sense this traditional knowledge are technologies too. Just you can see it in a different way. So it’s really important to make sure this knowledge is not lost for the benefit of everyone. And so did your work with this river lead into you starting to work with Native Land Digital or was those separate projects?

TR: I think I found Native Land Digital a couple of years ago just because of my interest in mapping and how do we start to do this from an indigenous perspective. And I fell into finding it. Looked online and saw that they were looking for people to work with as well. So in other words, I stalked them and applied for a job there as one of the research team. And so a year or so later, that’s when I got the job. And was very too as well because it gives you an excuse to delve deeper into these ideas of what is mapping for indigenous people.

AM: So for our listeners who maybe are just hearing of Native Land Digital for the first time, it’s been around I think something like five years. And the website that they may have encountered is native-land.ca. It was founded in Vancouver. Actually, in my neck of the woods up here. Or you could do a web search for Native Land Digital and find it. And this webpage, it starts with a map, but there’s so many more layers of information behind this map and in other pages on this website, but this map is where most people will land for the first time and where they’ve probably seen this. And if you haven’t seen it, I hope they will go there and take a look right now. In some ways, it’s been going viral. I’ve been seeing this map more and more in the last few years. I wonder just for our listeners who are listening along right now, could you describe a little bit about what it looks like when you land there? What the map looks like, what the website itself does?

TR: Sure. So it looks like a global atlas when you first land on the page. You’ll find there’s a disclaimer. So this is acknowledging the fact that even though we’re trying to map indigenous territories, this isn’t something that is black-and-white. That’s why you’ll find that there are many overlapping layers as people have been pushed from territory over history and had to be forced into other nations’ territories. We’ve sort of tried our best to include those stories, so. The founder, Victor Temprano, he is not indigenous. He’s a settler. And he had this idea as a project for understanding land and he wanted to get people to sort of think about the land they’re on and understand the First Nations who are there. And I think his first tagline was, whose land are you on? Sort of a little bit confrontational. [laughter] But I think he started to realize very early on that he would need indigenous people and indigenous thoughts and processes for this map. It’s one thing to just stick a map and stick some territories on there. He used open-source information to start building on that framework. And a lot of the information is sort of very euro-centric information in courts and whatever was available to him at the time, and he realized that he would need indigenous people’s opinions. So they built the board around indigenous people who were globally indigenous, which is fantastic. It gives a sort of– when we have questions because there are huge questions like what is indigenous? I mean, there are First Nations people all over the world. In Europe, the Irish had First Nations. Scottish, Spanish. We’ve got people from all over the globe saying, “Hey, we’ve got a First Nations too. Put us on the map.” So for us, the project has sort of expanded into thinking around what is indigenous. What does it mean to be indigenous? What does land mean? All these really deep, in-depth questions that we don’t even claim to have answers for. We’re all on a learning journey, most of us, having to re-learn our ancestral knowledge. Knowledge that we would have just been born into being taught prior to colonization for a lot of us. So it’s a huge learning journey and this disclaimer states that. And legally, the map can’t be used to enforce territories because it’s a shifting, moving, evolving, changing work.

AM: Yeah. And I think, as you said, it’s different for every part of the world. It’s different in different legal jurisdictions. For example, I grew up in the United States where there are not many sort of disputes about who owns what territory, but there’s ongoing enforcement of treaties. There’s ongoing transfers of land that are still happening. But I went to graduate school in Vancouver, Canada, where the vast majority of the native bands never signed treaties. And this is land that was never ceded. And of course, all the sessions that happened in the United States were under threat of violence and they were not fair by any means. But the fact that some groups still have that leverage of having never signed away their land, even under force, there’s so much more that– uncertainty can be powerful. It can be important to say, “We don’t want to actually put down our territory on paper yet.” And I’m wondering, is that something– this question of what can and can’t be mapped or what should or shouldn’t be mapped. That sounds like it does come up and is constantly a live question in this project. What are the things that maybe should never be put on this map or not on a public map, at least? Yeah. Ongoing discussions on that regard happening, I imagine?

TR: Oh, yes. [laughter] It’s a continual ongoing discussion. For us, it’s a huge responsibility. We don’t come at this lightly by any means. We can feel that weight literally on ourselves. There are just two, three people working on the information that comes in from tribal nations. And in doing that, we’re aware that we’re being given some really sacred knowledge sometimes. And so we feel that and we have to be aware of that. And we’re in the process of figuring out a framework and procedure so that we can actually put it on the map as well so it becomes very transparent to people who aren’t indigenous who are looking at the map. We want the map to feel like it’s living like the land. So when you’re reading these territories or clicking on these pretty colors and translucent layers, you’re going to have a better understanding that the land is not a resource to us. It is that body. It’s our ancestor. We’re looking at ways that we can transition the map into something like that, to have that better feeling of that living body. We also make sure that people know that information they give to us, please let us know what you want us to include on the territory page itself. Because once you click on the tribal territory, it’ll take you to another page, and there often will have a website or the resources that we use to map that territory to add that polygon shape to the map. That in itself is a huge responsibility. Because if that shape doesn’t look correct, we’ll have tribal members that email us and say, “Hey, this is incorrect. We’re currently dealing with legal issues and you putting this out there is wrong.” So it’s by no means something that we take lightly. And we have to be really sure that we’re dealing with this knowledge correctly. So in Māori, we call it tikanga, which is the correct procedure of doing things. The correct procedure for knowledge, how we take care of it. We understand that we’re kaitiaki, which is the word for caretakers. And yeah, we take it seriously. But we’re dealing with huge issues here that aren’t simple or straightforward.

AM: Yeah. I think once information is on the internet, it’s so hard to get it back, or to get the disclaimer or to get the edited version into people’s hands. I tend to follow usually on the side of these arguments the information wants to be free. I’d rather have open-source as much as you can. But I recognize there’s so many times where that can put people in danger or it can really compromise traditional knowledge. That sometimes we have to find these technological, legal, cultural, social solutions to keep the information where it ought to be. And I saw something really interesting you shared about creating software licenses or creative common style licenses where to use or possess even some off this information you are signing up for a particular legal license to say that it will be protected and used in certain ways, which I thought was fascinating. Another way of putting these traditional and indigenous needs into the framework that is maybe inherently agnostic to them, but trying to fight back within that framework.

TR: I think it’s so important as well to put it out there. I mean, if you look at AI in generative data, I mean, I’ve been looking at it from the point of view as an artist, generative art is just gathering art based on your command of what you input and it’ll bring you back an image. So I’ve been testing it out using the words Māori patterns and things like that, and text as well. So whatever you put there, AI will pick it up and homogenize it for someone’s work. And generally, it’s for marketing or something like that. So it’s so important these days. But I think the main point about that is, it’s down to us as people, and that’s people of all cultures and nations, how we use the internet. How we use information. Is there honor in what we’re doing? Is there respect? I mean, for Māori, there’s the word manaakitanga – and it’s one of the most important concepts – is how you’re treating people. Are you treating them with respect? Because that respect comes back to you and it grows your mana. It’s grows your self power, your self-awareness by respecting other people. And that’s how we treat the land as well traditionally. I mean, there are occasions now where tribal nations or indigenous people do think of the land as resource and that’s to help fund feeding the people. So there’s always that conversation that you’ve got to have with yourself, your ancestors, your lands, and try and figure it out. And I think that’s where we are today, trying to figure it out, how do we move forward.

AM: Yeah. I like that. And the idea of respecting other people with how you use information or their information or information about them. There’s also just this aspect of respecting yourself when you use information. And I like the disclaimer on this page where it’s just like, “Think critically when reading this map.” And really, I wish every webpage had that at the top. Just not think that you’ve got the answer just when you first glance at the page. And this is one of the other ways that this website is dealing with how to map uncertainty in a really interesting way. How to use a map and make a map that pushes against the way maps are often typically used. So we talked about how all of these territories are drawn sort of transparently and overlapping each other and you get this sort of blurry effect. How there’s just constant links to learn more. Just don’t think that traditional– see, I keep using traditional in different ways. Traditional indigenous, but also traditional Western way of thinking about maps. That maps from this kind of European-centric mindset is, once you put a name on a map and draw a polygon around it, you effectively know everything you need to know about that. You can bargain with that place, you can claim it, you can give it away to somebody else just because you’ve made a shape on a map. And this map, the Native Lands Map, is trying to use polygons on a map, but pushing against that easy feeling that you just know the answer once you see a map, which is really interesting the way it’s being done.

TR: But that’s, I think, is with the contemporary world, everything’s fast. It’s got to be done quickly. The box needs to be ticked. We’ve done it. Great. Let’s move on. So I think it kind of asks for time as well.

AM: And that’s also making me think of another thing I wanted to ask about was the practice of land acknowledgments. Which is something that is where I think a lot of people are encountering this webpage for the first time or hearing people reference it, probably a lot of our listeners might come from parts of the world where they haven’t heard that many land acknowledgements. It’s definitely growing in practice. It’s like when I started school in Canada in the mid-2000s, I started hearing land acknowledgements quite a lot. I don’t think I’d heard any before when I lived in the States. And then when I came back around 2012, I started to hear them more. And a land acknowledgement is, basically, you’ll often hear them at the beginning of a public event or in someone’s introduction of themselves. Like I might say, “I’m recording this podcast from the traditional lands of the Lummi and Nooksack Nations and the Coast Salish people here in Bellingham, Washington. The people who have lived on these lands since time immemorial.” I would hear a structure like that. Basically, recognizing who has been here, who still is here. And especially in Canada, we would say that this is the unceded lands of the Musqueam people, for example, in Vancouver. So people want to be able to do that. And it sounds like that was some of the founder’s initial intent was to make it easier for people to answer that question and learn about whose land are they on and make acknowledgement like this. I see also that the website has a whole page about why you should do a territory acknowledgment and how to do that and how to learn more. Has the organization been doing more to support this concept or any thoughts you have on this growing practice and the importance of it?

TR: I think definitely the popularity of the site has increased with the increase in land acknowledgments. And it was Victor’s intention to bring that awareness of indigenous peoples and their lands to non-indigenous people. And I know that we hear a lot from non-indigenous who are thankful for the site and they’ve learnt a lot. And I think from our perspective, especially as indigenous people on the team, we hope that people will use Native Land Digital as a starting point, as a really basic starting point, to find the territory they’re in, find the tribal nations, click on some of the resources that we have, but the important thing is to actually go to those nations websites and learn from their voice. Because we know that it’s not our voice that speaks for all nations, so it’s really important to hear what those people have to say themselves. Hear their stories. But in saying that, it’s also really important to understand that there seems to be a bit of a misconception that people can just expect indigenous people to give their information freely. To talk about their nation freely. They have time to do this. And a lot of nations are actually struggling to support our own people. Even if we’re not on the lands, we’re thinking about the people back home. And in, as you say, the high majority of the poorer environments, how can we move forward? How can we help them? So a lot of our nations don’t have time to sit here and be teachers and explain.

TR: So I think especially when creating land acknowledgments, rather than just making it something that’s just like the beginning to a speech, you tell the joke to loosen up the crowd sort of thing, I think it’s really important to – if you care that much – make sure that you understand those people and their voice, and then you can speak from an authentic point of view. Because as indigenous peoples, we really understand authenticity. And we know when people are face to facing us and just being very sort of superficial or doing things because they think they have to for your culture. I know it means well, but we can feel it. For us, for Māori, we generally have a karakia, which is the start to your ceremony. Because what it’s doing is it’s acknowledging the original atua. So the original Gods of the land. And that’s very important to us because if we don’t acknowledge our elder, then we’re not going to get anywhere with whatever we’re trying to do. If you come from that space of authenticity, you understand their stories, I think you’re going to make a much more meaningful acknowledgment.

AM: Oh, that is so, so important to hear. And that was getting at one of the follow-ups I was curious about. Because especially in western Canada, hearing more and more backlash that these land acknowledgments are just lip service. People are just saying them to get them out of the way or to look like they’re more woke. Or there’s also the other the other side of things with non-natives and settlers who might be too earnest trying to get involved but getting in the way and not actually listening to what local indigenous communities actually want or are asking for or what their priorities are. And yet it’s not supposed to be easy. It shouldn’t be easy for us who are non-native. There should be some work for us to take some initiatives, to educate ourselves, and not put all that burden on native people to do the educating. And yeah, and I’m wondering also just thinking about specific ways that non-natives could contribute to the Native Land Digital project. You noted how Victor, the founder, was non-native, but quickly brought in a board of Indigenous people from all over the world to help direct what gets done next. And I’m wondering what are the roles now or how can non-native people contribute and be involved at this point.

TR: Well, just talking about Victor, at the end of last year, he stepped down from the role – not officially or anything like that. Just quietly stepped down – and the board took over Native Land Digital. And that in itself kind of speaks volumes. Well, it speaks volumes to me. Just quietly stepping aside because he knew that the work he needed to do was done. And it was a huge amount of work. He used to do all the fixes. People constantly coming through emails and things saying, “No, this is wrong. This needs to be changed.” He did all this by himself. And I came from the research side, so I know how many fixes need to be done. It’s a huge volume of work. So the fact that he gifted that so quietly. And it’s gifted to indigenous nations, not just non-indigenous. I mean, he started it with this idea of bringing attention to, but I have received so many emails from nation members saying that finally they feel heard. Finally, they feel seen. Finally, they’re acknowledged when they write into us and tell us about things that need to be adjusted and this isn’t right. We’re really respectful about how we come back and we say, “We’re very sorry that that’s incorrect. We’ll change it as soon as we can.” I know at the moment we’re really weighed under by– the International Indigenous Day brought in an absolute storm of information that needs to be added, corrected, amended. So we’re running a bit behind. It’s a huge and exhausting role. So we do have a Patreon, I think if people want to help.

TR: But I think for the most part, the important thing is understanding that indigenous nations themselves know what they need. They know what’s needed within their communities. And each community is different. There’s not this idea of homogenized Māori, homogenized native American. I’m doing the quotation marks. But each tribal nation with its own name, its own creation story. And we understand that each nation story is important to them and each nation knows what they need. So when people want to help, I think it goes back to that finding out, listening, reading. Understanding the nation that the land where you are. And in its most basic form, what our lands need is rejuvenation and our lands need that acknowledgement in themselves, the land itself. So if you’re kind of at a loss, you’ve tried to make contact and you haven’t heard anything back, I would say, what’s in your backyard? Are you talking to those trees? Are you understanding the biodiversity of that land? Are you planting it up? Are you looking after it? Because for us as indigenous, if the land is being taken care of, you’re a winner. If you’re putting in the work, if you’re putting your hands to the soil, that’s when we’ll love you because we can see that. Our value systems are very different, but most of our indigenous nations – before colonization – for us, the richest person – that’s male or female – of a tribal nation was the one that brought the most food for the rest of the tribe. They were always the greatest chief, the one who were thought of as the richest, not in the terms of money, but in the terms of as giving value, that manaakitanga, the respect, and they were feeding the most people. And that comes back to the land. Understanding the land, how it works. I mean, for our Māori traditions, our ancestors would garden in a garden for three growing seasons and then they would leave that earth for 7 to 10 years. So that’s regeneration. That’s regeneration working. And that’s ancestral knowledge for us today – we really need it – to understand that. That the land does need to have time. It needs to be taken care of. And I think if you can understand those principles, those basic principles, you can really be helpful to indigenous people and the original people of that land.

AM: And one thing you mentioned there that got me thinking was just talking about recognizing the specificity and that none of these native groups, even if we have one name for them, are usually not one homogeneous whole. That it’s down to very, very small, but distinct communities. And it’s also making me think about how putting all of these things on one map on the web, which is kind of this globalized, totalizing thing, is something that always needs to be done cautiously and making sure that it doesn’t– everything get forced into the same similar kinds of buckets. One specific way that that could happen is just sort of the tyranny of the English language, for example. That so much that happens on the internet has to be done through English. And I’m speaking as someone who can barely speak anything other than English. And here we’re having a podcast in English. But it seemed that the website in particular has been adding more languages and that you’ve been bringing Aotearoa language into this podcast, which is very welcome and we really appreciate that. I’m wondering if you can talk more about the importance of languages. There’s a language view of the map, but also the translation of parts of the webpage into other languages. Just recognizing that half the world’s languages are at risk of going extinct and that preserving language is a way to preserve culture and knowledge.

TR: That’s another thing that we hear a lot. The language is so important. Elder generations are sort of passing away will all these old stories. And a lot of them will have this opinion that, “It’s a silly story, dear.” That’s what I hear a lot from our grandmothers. And they’ll say things like, “Oh, you’ll think I’m silly.” But the stories that they’re telling us are interwoven with our histories and the knowledge that we need in order to move forward. And unfortunately, especially with colonized nations, our elders, a lot of them will be of the opinion that what they know is silly compared to science or something like that. A lot of them will be a little bit embarrassed to talk about the old knowledge because that’s the way they’ve been made to feel. They were punished in school for speaking about their old ways. So what we can keep of our language and our sounds is so important because that’s our belonging to the land. It’s our connector. And a lot of us who have traditional knowledge within oral histories, it’s more about the sound, and that’s what connects us to the land. It’s not exactly the word. For te reo, our Māori language, a lot of the times the English translation is one word, but the word will mean so much more. There’ll be a layering of what it means. And it’s interwoven with connection to land and survival. So it’s very important that we keep those sounds. And the knowledge and the histories that are also kept in songs is not just speaking. It’s songs, dance. For a lot of nations, there’ll be instruments involved. And those sounds are also that language that connect us. So for us with Native Land Digital, we’re hoping to add layers of sounds as well. So layers of greetings. And we’re hoping to collaborate with a couple of other groups in partnership so we can do that. We want to bring life to the map. So visual, and the songs and the stories. Those that people want to share, that is, so that other people can get a better understanding of how each nation connects.

AM: And that also transitions to one thing I wanted to ask about is what else is happening next with Native Land Digital? As someone looking at the site from the outside, it looks like there’s so much more to be done. Obviously, they keep collecting information, but sort of the technical aspects of making the map work look sort of done and that it’s an opportunity to start adding new features to broaden and spread in different directions. And also, the fact that you’re coming in as the new executive director may be an opportunity to look at different directions for the organization. So I’m wondering if you have anything else that you can share with us about what’s coming next for the project.

TR: Yes. We’re really excited because, yes, it does look like an accomplished map. [laughter] But for indigenous folks, it’s rather dull. So like I said, we’re wanting to add those layers of audio. Get the languages really more visible than the view of it. We want it to feel alive. It’s constantly evolving. And that’s how we understand our knowledge systems are a constant. It’s not just set in stone. The outlines drawn around it, it’s done. It’s evolving just like the natural world evolves. We want that map to reflect our ways of being, our knowledge systems. And that would be bringing more sound. Making it more visual. Making it feel alive. Because if you imagine all those many different cultures on there with all their visuals, a lot of people are uploading to YouTube now to help people understand how you speak properly the tribal name. Because that’s the other thing, a lot of the tribal names are incorrect. We’ll get nation members who email and say, “Hey, get that name off there. That was made by a White man.” And in their language, it could mean something really derogatory like little brown man, and they’ve put that in their language. So you think about a psychological attack daily that you have to live with. We’re really pushing to try to reach as many people. And we just love it when nation members write in to us, even if they’re like, “Hey. [Get it off?].” [laughter] Initially, they’re really angry. We’re sort of like, “Oh, we’re really sorry, but we only had open-source information. We didn’t know.” We have to apologize a lot.

TR: And for indigenous people– I know for Māori; we’ve got this word which is hūmārie. And if you’re a leader, you have hūmārie, which is humility. So you understand from the get-go because you already know you are the younger to the land, so you should have that hūmārie within you. The humility to understand. And when someone’s really angry, that’s because they’ve got a reason to be really angry because of our indigenous past colonization; all the horrors, atrocities that have happened to our peoples. And we like to think of them as brothers and sisters. Because for us, the main thing is whānau. Family. So whanaungatanga in Māori means to build family relationships. We do this with the natural world. We do this with each other. We grow that respect, the manaakitanga, and we grow because of it, personally. So how are we in service? And I know many indigenous nations are the same way. How are we in service to each other? It’s not about that individual. It’s not about me or you. It’s how are we working in service. Not for ourselves, but for our future generations. And I think that’s a great way to also look at environmental issues and climate change and start by rethinking how we’re looking at things.

AM: That’s great. Thank you for all that. And we also have barely scratched the surface of all of the interesting things going on in your art practice as well. And I’m just wondering, hopefully, this role at Native Land Digital won’t take up all your time and you still have a lot of your other threads on the go. Our listeners should check out your website at fogandmoonstudio.com. There’s so much interesting stuff there. Is there anything you have that you’re excited about that you have in progress or that is starting up soon that you’d like to share about? I know a lot of us at Stamen are into games and I saw a hint of some kind of game that you’re working on that involves a map and ecosystem interactions. But whatever you’re excited to share with us I would love to hear about it.

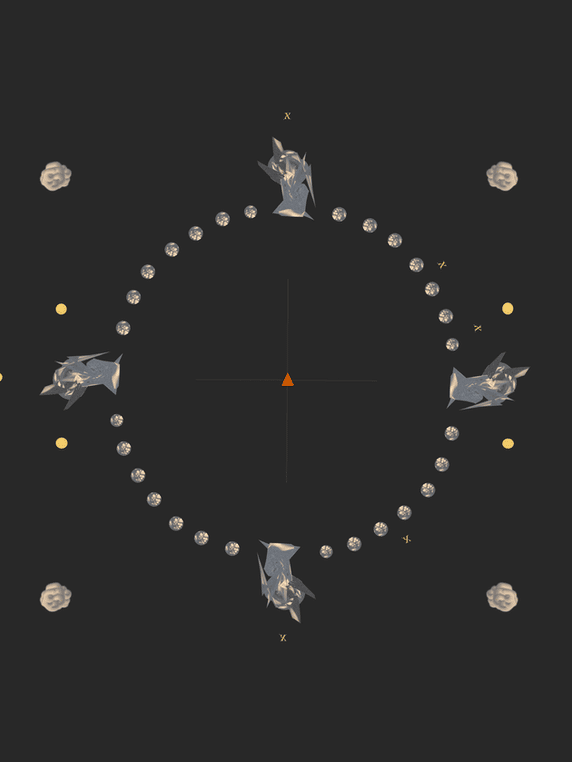

TR: Oh, it is very exciting. One of my art projects was to look at ways that we could bring attention to some of the viruses that are occurring in our forests, like the English ash tree. Some of our major trees are being affected by viruses. Fungi, the varieties are sort of being killed from the inside and they can’t regrow, which is very serious for us. What inspires my work is my great-grandmother’s rongoā medicinal plant recipes. So that’s the basis to my work. And to understand that some of those plants which we story to– the Kauri tree is our Tāne Mahuta, which is the God of the Forest, and that tree has kauri dieback. So for me as and an indigenous person and as an artist, to see that happening out there in the world is a very big warning sign that we need to do something. We need to change. And I was thinking along those lines of, how do we reach quickly people to make them understand that? And of course, it’s gaming. I mean, our youth, they love games. They love visuals. They love sound. Being immersed in other worlds, other universes. Being away from what’s happening. So I thought, “Well, how about if we build this game environment around the ngahere, the forest? We teach people practical things.” You come across a leaf of a tree and you understand that that leaf will help you if you have a headache. So you’re learning within a virtual environment. You’re learning practical things. How to take care of the forest. And also, there’s a map involved. So it’s mapping the ngahere, the forest, and moving through the species and learning about the different viruses and troubles of the forest. And before you start the game, there’s a karakia. So if you don’t click on the karakia, the game doesn’t open up and the forest won’t open up for you. So that’s getting back to that thing I was talking about, the acknowledgment and understanding of the natural world as your elder. And so for me, the most exciting part of that is I have another new role as a lecturer of Mātauranga Māori at our Victoria University here in the capital city, and I’m incorporating the knowledge that I’m learning from all our indigenous nations with Native Land Digital and that has become my research. So I’m learning about those sounds and the basic understanding of those sounds and how we can share that so we can all get on board and take care of our natural world.

AM: That’s fantastic. Well, thank you so much for your time with us today. Is there anything else that you want us to know about this project or really anything that you’d like to share with our listeners that we haven’t covered yet?

TR: I think the most important thing is to just be open. Open to learning, hearing, understanding, connecting. And my grandmother used to say, “Wairua to wairua.” So spirit to spirit. Speak to people and communicate with people like that and it’ll come back to you tenfold. So I think just be open and that’s the best thing you can do.

[music]

Thank you for listening to Pollinate. Thanks to Tanya chatting today! This episode was written by Alan McConchie, Laura Gillen, Ross Thorn, and Shirin Makaremi. Music for Pollinate was created by Julian Russell. You learn more about Native Land Digital and the indigenous communities where you live at native-land.ca. There you can also find out how to support the project via financial donations and you can also find more of Tanya’s work at fogandmoonstudio.com.

If you enjoy the show, please review us and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts and share it with colleagues and friends! If you have a favorite part of this episode, let us know on Twitter @stamen or on our new Mastodon account at vis.social/@stamen. And tag us using #pollinate or #pln8. For a summary and full transcript of today’s conversation along with visuals we discussed, check out the blog post at stamen.com/blog.